Transforming Northwood Plaza: A Shopping Center Reveals Lessons About Community Development

May 6, 2020 | By Jen Collins and Ryan Goss

This is part of our ‘Impact in Action’ series, co-produced with the Centre for Public Impact, highlighting innovative models and lessons for driving positive community impact through investment and development projects across America. Read the other stories from Kannapolis, NC and Merced, CA.

Below the surface of disrepair, a vision of hope

For the last two years, it would be easy to drive by the Northwood Plaza Shopping Center without noticing it. If you caught a glimpse as you passed through Northeast Baltimore, you might notice a pair of broken pay phones, one listing 45° to its side. You might notice the row of boarded-up storefronts.

You might not realize that the once segregated shopping center was the site of historic Civil Rights activism. You might not realize that a renowned academic institution is producing the next generation of leaders next door. You might not realize that there’s been a decades-long struggle to create a new vision for the complex, and that this vision is about to become reality.

Below the surface, the story of Northwood Plaza reveals important lessons about the long and often difficult process of community revitalization. As neighborhoods across the nation look to rebuild following the economic and social devastation of COVID-19, reflecting on these lessons is as important as ever.

Guiding Principles for Equitable Investments

Alongside its partners, the Beeck Center created the Opportunity Zone Impact Reporting Framework, a voluntary guideline designed to define best practices for investors and fund managers looking to invest in low-income communities through incentives such as Opportunity Zones (OZ). In the sections that follow, we explore the projects in Baltimore, extracting the lessons to help communities and investors bring the five guiding principles of effective and equitable investments to life:

-

- Community Engagement

- Equity

- Transparency

- Measurement

- Outcomes

To prioritize equity, it is critical to understand a community’s history

The shopping center’s deserted storefronts reveal the truth that prosperity has not been evenly spread across the city of Baltimore. Only four of Baltimore’s 200 census tracts have per-capita incomes greater than $100,000, and in these tracts, only 5% of residents are black. Yet, in Baltimore City overall, 62% of residents are black.

This disparity is rooted in a long history of systemic racism in Baltimore and across the nation. When Northwood resident Paula Purviance first attended Morgan State College in 1968, the communities in Northeast Baltimore were still in the throes of a turbulent racial integration process. “To walk along one of the main roads to campus, many students felt uncomfortable and minimized,” Ms. Purviance remembers. “As a result, students would walk to the campus by way of the rear alley of Cold Spring Lane.”

Throughout the middle of the 20th century in Northwood, as in many neighborhoods across Baltimore, white property owners used racial covenants to prevent property from being sold to or occupied by black and Jewish residents. Though the Supreme Court struck down these covenants in 1948, the language still remains in many official property records.

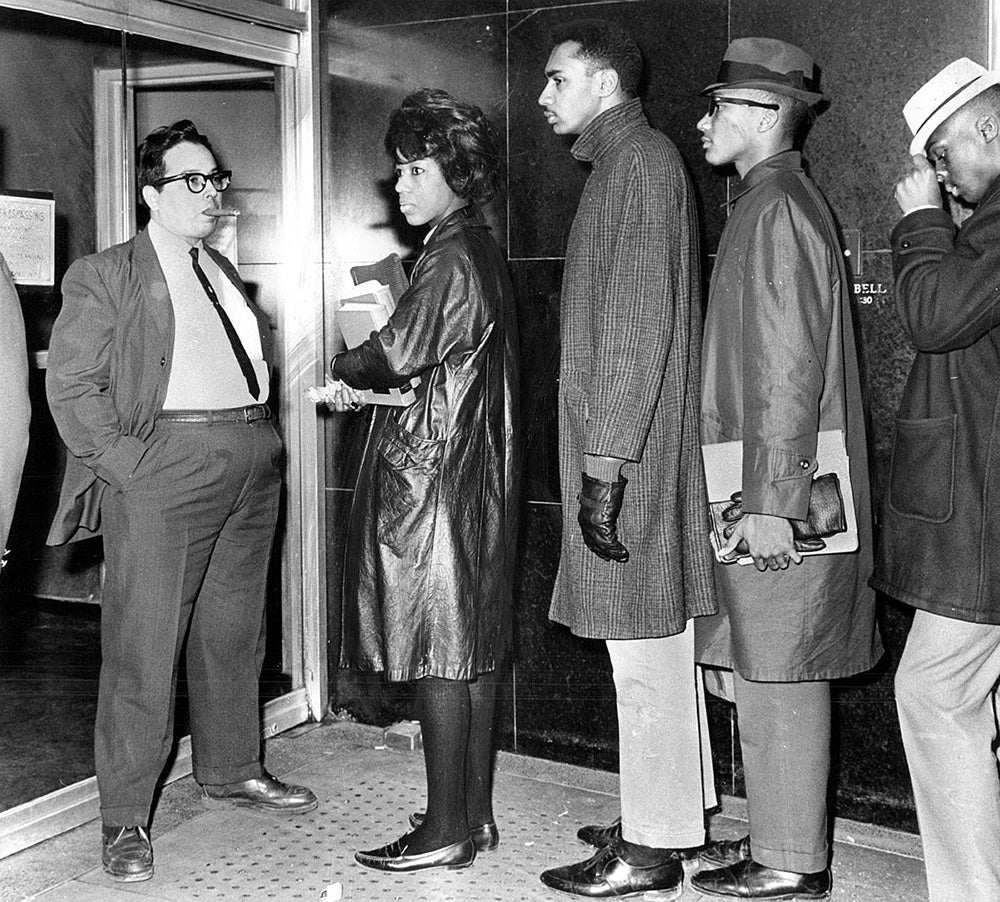

As the Civil Rights movement spread across the nation, Northwood Plaza Shopping Center became a hub of activism. In 1955, an interracial group of students from next door Morgan State College – what eventually became Maryland’s largest Historically Black University – were denied entry to segregated Northwood Theater. In 1963, the theater again became the site of anti-segregation protests, where hundreds of students were arrested and charged with trespassing and disorderly conduct.

These remaining markings of institutional racism reveal the barriers that have long prevented people of color from having a voice in, owning, or making decisions about their community in Northeast Baltimore. This reality often gives rise to skepticism in residents when investors try to upgrade community assets. “Oftentimes, there’s a natural skepticism and distrust within communities of outside or institutional investors who, either intentionally or unintentionally, disregard the best interests of the community and do more damage than good to existing residents and businesses,” notes Ben Seigel, Baltimore’s Opportunity Zone Coordinator. But with collaboration, cooperation, and accountability, Ben believes that there can be common ground.

Mistrust turns into a unified vision

While the Northwood Plaza Shopping Center eventually became integrated and overseen by new owners in the 1970s, the neighborhood still struggled with violence. In 2008, former Baltimore City Councilman Ken Harris was shot and killed outside a nightclub in the complex. In the decade following, the death of Councilman Harris lingered over the property and by 2017, Northwood Plaza had fallen into disrepair.

Before the businesses officially closed, a struggle to reimagine the shopping center was decades in the making. “There was massive mistrust of all the different stakeholders when we first started this project,” remembers Mark Renbaum of MLR Partners, the initial developer involved in re-developing the complex. “When I first got involved in the project, I thought it was going to be easy – and that everyone would embrace change necessary to redevelop Northwood into a first-class destination. But what we learned is that there are a lot of stakeholders with a lot of different visions for what they thought it could be. And all of those voices needed to be heard first before anything could get done.”

By all accounts, the over 20-years of negotiations among community leaders, Morgan State leaders, public officials, and the owners was exhausting and contentious. And yet, with patience and compromise, political interventions and financial subsidies, Northwood Plaza will soon become Northwood Commons: a new $58 million shopping center with retail and restaurant space, as well as office space for Morgan State University. At the November 2018 groundbreaking ceremony, Morgan State President Dr. David Wilson remembered the students once arrested on those grounds. “They could see this location from across the street, but they could not experience it.” 60 years later, Northwood Commons intends to become a safe and vibrant place for students and residents alike.

Theory of Change: Creating Dynamic, Livable Communities

The story of Northwood Plaza reveals the often overlooked importance of dynamic, mixed-use spaces in underserved communities. In the last half century, many community developers have focused poverty-alleviation efforts on the development of low-income rental housing. While affordable housing remains critical for millions of Americans, this approach has done little more than concentrate low-income families into smaller geographic areas farther from opportunity. The resulting concentration undermines access to good jobs, healthy food, and safe spaces with diverse commercial options. This consolidation, in part, fuels the cycle of economic inequality that leads some neighborhoods to thrive and others to flounder.

Meanwhile, some cities are experimenting with new ways of creating economically integrated neighborhoods. Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo introduced the idea of a ‘15-Minute City’, suggesting that every resident should have their needs met within 15 minutes of their doorstep. This bold plan will require a sort of “anti-zoning effort” across the city to improve access to the essential functions of life, such as work, shopping, health, and culture. Similarly, East London’s Every One Every Day initiative is working to radically expand community-organized social activities, training, and business development opportunities within walking distance in one of London’s lowest-income boroughs. These cities are recognizing that “hyper-local” approaches to community development can reduce barriers to unlocking economic and social vitality.

A new space to meet community need

In Baltimore, Northwood Commons will fill some critical needs for Northwood residents and students. “This is a food desert,” says Sidney Evans, Vice President of Finance and Management at Morgan State. “I have to drive three miles to sit down and have a nice lunch with someone.” Since joining Morgan State in 2014, Sidney has participated in the negotiations to bring Northwood Commons to life. “This shopping center is going to give the community much more flexibility to fill their basic needs.”

Beyond providing food and retail options, the space aims to foster community. The forthcoming Morgan State bookstore “will create a venue for socialization,” Sidney predicts. “It will give our community a place to talk about social issues and civil rights issues, a place for older citizens to mingle with younger people and vice versa.” Northwood Commons will also contain the Morgan State public safety department, providing a feeling of safety and security to the area. Evans hopes this safe, vibrant space will help encourage Morgan students to remain in Northwood after graduation.

Effective community development projects address clear areas of community need and have investors commit to measuring outcomes over time

Evidence of community need can be found by consulting resources such as the U.S. Census Bureaus’ Data Archive, and from community engagement activities such as town hall meetings, listening tours and community needs assessments.

Collaboration is key

In many under-served communities, investors fear that creating these types of dynamic multi-use spaces will not be financially viable. Dave Bramble is the Managing Partner of MCB Real Estate, one of the developers behind the Northwood Commons deal. Dave, who grew up just miles from Northwood, has experienced the challenge of getting these projects financed, but believes that, with the right ingredients, impactful development projects can get done and generate returns.

These deals often require sizable anchor partners – like Morgan State – to invest in the growth of a surrounding community; they require patience to create a project vision that meets a critical mass of community and financial needs; and they frequently require subsidy from the state, city, or other sources. “Deals in under-invested communities do not work in a vacuum” Dave notes. “To make a non-traditional real estate project actually work, you need other types of support – in this case, investment from a public university, funds from the state in the forms of bonds and grants, infrastructure support from the city, and federal tax credits.” Either with direct public subsidies or incentives, such as those offered by Opportunity Zones, these types of deals can overcome the seemingly insurmountable financing barriers and generate returns.

Lessons Learned

Opportunity to Impact: An Investment Assessment

The Centre for Public Impact – alongside its advisors at Georgetown’s Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation – set out to better understand the process of generating positive community impact through private investment and development. The resulting tool, Opportunity to Impact, is a simple, yet rigorous guide for evaluating an investment project’s potential for positive impact. Some of the findings from this research is embedded in the section below.

While Northwood Commons will not be completed until the end of 2020, the journey has yielded valuable learnings for those engaged in meaningful community development projects.

Engaging and defining “community” is not easy, but it is essential to a project’s success

Most people involved in community development will acknowledge the importance of engaging the community. But defining – let alone engaging – the community is rarely straightforward. There are over 20 neighborhood associations in Northeast Baltimore, each representing diverse subsets of Baltimore residents. Multiple of these organizations were directly involved in the Northwood Commons negotiations and they often had vastly different visions.

The largest disagreement centered on whether Morgan State student housing would be part of the complex’s future. These differences seemed destined for stalemate until the involvement of State Senator Joan Carter Conway. Senator Conway introduced a bill to block the student housing proposal and soon became an important broker for talks between the community organizations, the university, the owners, and developers.

Private developers and investors also have a critical role to play in this community engagement process, but do not always show up to the table. “The reality is that if you don’t need zoning, or you don’t need anything, it’s rare that developers will engage with the community,” notes Dave Bramble. But these forums provide information that is critical to a project’s success. “When you go to these community meetings and you really get to know these people, you realize that what you assumed they want or what they might be okay with is not necessarily true,” reflects Mark Renbaum. As the Northwood Commons project demonstrates, identifying, listening to, and compromising with community stakeholders can be the difference between continued inaction and project getting off the ground.

Meet some of the people involved in the Northwood Commons project.

Building a vision requires compromise, transparency, and assurances of accountability

Countless proposals for the shopping center circulated since the Northwood theater closed in 1981. At various points, ideas included a new hotel and conference center and a community-led design center. But each of these proposals failed to gain steam, for one reason or another, often forcing working groups to start over after years of negotiation.

Ultimately, building consensus and gaining buy-in required compromise and transparency among all parties. “It’s about being honest,” Dave Bramble notes. “When I say honest, I mean telling people stuff they don’t want to hear. Everyone might not get everything they want because, ultimately, the math has to work.” Sidney Evans knew Morgan State had to understand this perspective. “We understood that investors need a viable project, one that has a direct impact on the community, but also generates a fair return on the investment.” Evan adds, “as I talk to other University Presidents about these types of projects, you can’t just come up with any type of development project, it must add value to the community and to the investors. Capital just isn’t free.”

Ultimately, navigating these conversations required an honest broker: someone – or something – to ensure accountability. Together, developers and community leaders eventually drafted a Community Benefits Agreement. This contract between community groups and the developer guarantees certain amenities and mitigation of certain risks. With concrete accountability measures and a bold yet achievable plan in place, the long talks began transforming into action for Northwood.

An Honorable Path Forward

Beyond filling commercial needs or achieving returns, Northwood Commons is about pride. As Ms. Purviance remembers, “the community residents felt there was no pride in the look of the shopping center.” But she was motivated to help build a vibrant and safe community for her child. This inspired her to again become affiliated with the community association, volunteer as one of the co-chairs of the Northwood Shopping Center Task Force, and become the President of the Hillen Road Community Association. At the November 2018 groundbreaking ceremony, Ms. Purviance addressed the crowd: “This morning gives me a ray of hope, and we need that ray of hope… Each of us here today, is looking forward to what can be a grand shopping center, that will be seen as an asset to the Northeast communities and to the city as a whole.”

Jen Collins is a Fellow-in-Residence for the Beeck Center. Follow her on Twitter @JenCollins24

Ryan Goss is a Senior Associate at the Centre for Public Impact, where his work focuses on helping governments and their partners improve people’s economic mobility and flourish over time. Follow him on Twitter @R_Goss1