Digitizing Remittances in a Pandemic: Recommendations

October 15, 2020 – By Shaily Acharya

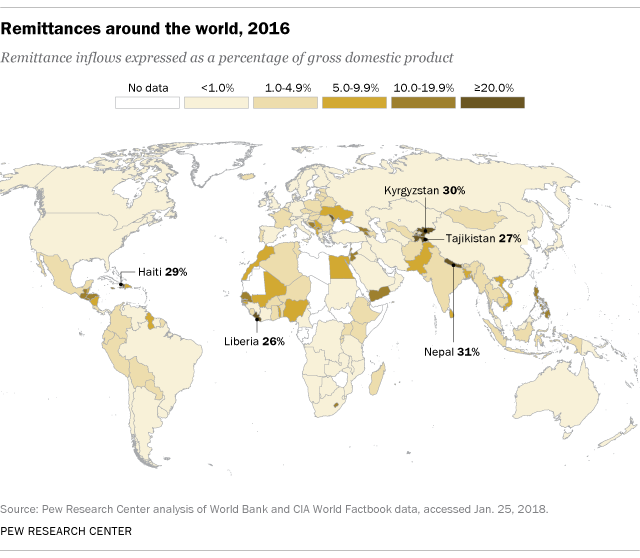

Every month, my dad sends a portion of his income to his parents in Nepal. This transfer of money, typically sent back to a person’s home country, is known as a remittance payment. Nepal’s remittance inflows account for about a third of their GDP, and has a bigger impact on the country’s development than foreign direct investment and net official development assistance. Without realizing it, I’ve been part of one of the largest remittance economies in the world for my entire life!

My grandparents were fortunate enough to work in formal industries their whole lives, which gave them access to regular banking services and technology, making the remittance process much easier. However, in Nepal, 70% of the economically active population is involved in the informal economy, which means they face barriers to accessing key financial services. This problem is not unique to just one country – globally, unbanked and underbanked populations face obstacles when trying to access both financial and digital services.

As more of these remittance payments move electronically across the globe, three main obstacles must be addressed to include unbanked and underbanked populations: Infrastructure, Information, and Trust.

INFRASTRUCTURE: Underbanked populations are more likely to lack critical resources, such as a phone with banking capabilities, a bank account linked to their phone number, language inclusivity in mobile applications, dependable internet connections, etc. Even if the remitting population has access to the basic infrastructure (through their workplace, for example), it is very likely that the recipients of the payments will not have adequate resources to allow the person-to-person transaction to be completed. This problem is systemic globally as women and minorities around the world bear the brunt of this issue far more than other populations.

Public-private partnerships between governments and technology companies are needed in order to give the capacity to digitize remittance payments to underbanked populations. For example, India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) allows for digital remittance transactions on feature phones, not only smartphones, opening the system to a larger portion of the population. While the public sector is effective in creating initial infrastructure policies, its risk-averse nature leaves experimentation to the private sector to come up with more innovative solutions, so taking some of these risks must be incentivized. For example, Vodafone in Kenya implemented M-Pesa, a digital payments platform that followed national regulations to bring unbanked populations into the formal financial structure.

The author goes deeper into the topic of digital remittances.

INFORMATION: Even if technologies are available to ease the process of sending and receiving remittances, much of the target population is unaware of them. And if they do know the technologies exist, they likely lack the basic financial and technological literacy needed to best utilize the tools, putting remittance application usage squarely on the fault lines of the global digital divide. For anyone who has struggled to get a parent or grandparent to use a new app to chat, imagine how much harder it gets when money is involved.

Technological financial literacy education would mitigate this issue. A field study by IDinsight and Good Business Lab (GBL) in Bangalore, India, looked at how different training sessions for female garment factory workers would change digital remittance usage patterns. Ultimately, they found that both group and individual training sessions on the use of digital payment applications to send remittances were effective. When the training is conducted locally, over a long period of time, in individual communities, it has the ability to truly transform how migrant workers and their families understand remittance technologies.

TRUST: The most common method of making payments among unbanked and underbanked populations is through informal networks of trusted local leaders, business owners, and merchants. The risks of this system are obvious – there is no way to ensure that the “middle men” of the transaction actually complete the job or if they take a portion of the money for themselves. Despite that, for those accustomed to this method of remitting money, it is very difficult to trust a mobile application to do the same job, especially if the benefits are not self-evident and the process is not transparent. According to Xavier Martin Palomas of the Digital Frontiers Institute, “even though, on average, online services are less expensive than cash-to-cash services, most remittance customers seem happy with their money transfer agent.” The issue of trust builds off of the lack of information, but there are a variety of other individual-level factors that are not as easily addressed.

Sometimes, even education and information are not sufficient in building trust in these unfamiliar technologies – the use of the technology by trusted individuals, however, can signal the acceptance of digital remittances in individual communities. If the current “middle-men” of the informal remittance pathways increase their use of digital payment apps, we will get closer to reaching the target population than training and education alone.

These obstacles to the digitization of remittances do not exist in isolation: in order to create effective change, all three must be addressed simultaneously, requiring large-scale collaboration between private sector foundations and businesses, community organizations, and government institutions, along with any other actors in the space. For my grandparents and millions like them, the need is obvious and now is the time.

Shaily Acharya is a sophomore in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. As a Student Analyst in the Fair Finance Portfolio, Shaily explored issues of equity and inclusion in our current financial systems in order to create a more even financial playing field for all.