Let’s Pay For A Social Inclusion Framework

September 16, 2020 – By Cristina Alaniz

Understanding key components that drive successful social service programs, specifically centered around workforce development training, is a theme that I have explored over the course of the last year. As a Student Analyst at the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation, I focused on a project, supported by the WES Mariam Assefa Fund, to identify approaches that could drive additional capital to workforce training and development of immigrant and refugee workers.

As the world enters its eighth month of the pandemic and ongoing economic uncertainty, vulnerable communities face increasing barriers to economic prosperity and social inclusion. During this trying time, the world must not forget to continue to support these populations and equip them with the tools necessary for survival. Refugees are a group especially at risk. According to the United Nations High Refugee Commissioner (UNHCR) the current global refugee crisis has hit a record high of approximately 79.5 million forcibly displaced people. As the pandemic hinders the ability of countries to welcome refugees and provide adequate resources, digital gaps and disparities in access to healthcare will likely heighten the frustrations and needs of this population.

Resettlement States provide refugees with legal and physical protection, including access to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals. (UNHCR) By way of this, the States adhere to the delivery of a “social inclusion framework” that creates opportunities for refugees to develop their ability to reach self-sufficiency. According to the World Bank, social inclusion barriers include not only legal systems, land and labor markets, but also attitudes, beliefs, or perceptions. This is crucial, as cultural barriers are predominant factors that may prevent immigrant and refugee communities from reaching social inclusion rapidly or at all. As resettlement and welcoming efforts are made around the world, societies begin to recognize that a social inclusion framework is multi-faceted and blends with the economic development of the State.

Unfortunately, the health of our global economy is weak and is predicted to shrink by at least 5.2% this year. U.S. unemployment continues to fluctuate and stands at 8.4%. These uncertainties decrease opportunities for vulnerable populations, as well as pose a major problem for States; a capital problem. With funding fragmented across government-funded programs and an expected uptick in demand for social services from both refugees and national citizens, how can States look to private funding to help solve the capital problem and create a sustainable social inclusion framework? As impact investors seek to use their capital to address structural barriers, can we rely on them to make blended capital (a mix of government, non-profit grants, equity investors and lenders) a more permanent solution for funding social services programs?

A Solution: The Social Impact Bond (SIB)

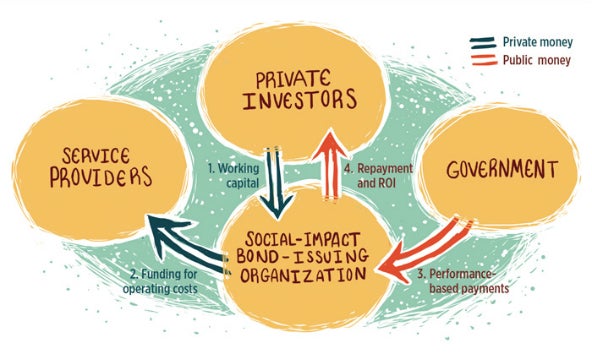

The Social Impact Bond (SIB), “is an innovative financing mechanism that shifts financial risk from a traditional funder — usually government — to a new investor, who provides up-front capital to scale an evidence-based social program to improve outcomes for a vulnerable population. If an independent evaluation shows that the program achieved agreed-upon outcomes, then the investment is repaid by the traditional funder. If not, the investor takes the loss.” (Urban Institute)

Over 175 SIBs exist around the world. These vehicles have largely focused on financing social welfare and employment projects and can help reduce the cost of public services for taxpayers. The U.K., home to the first SIB (2010) has the largest market exposure, followed by the U.S. As of 2015, SIBs have gradually made their way into the developing world, where they are often called “Development Impact Bonds”. The average life of a SIB is typically 2-5 years and the number of individuals served varies by motivation for project, project objective and issue area. As an example, we look to Nordic efforts, where social inclusion frameworks are well thought out and incorporate beneficiary feedback. Finland, a country who sought impact investing initiatives, designed a SIB that solves for rapid employment integration of immigrants and refugees, satisfying a key measure of its innovative social inclusion and participatory framework for arriving immigrants and refugees in Finland. This project also helps the country reduce resettlement/social expenditures.

Finland: A Case of Compassion for Inclusion of Immigrant Blue-Collar Workers

In Finland the admission limit of 750 refugees is set in consultation amongst various government agencies. The “Koto-SIB” program is an integration social impact bond structured to help with integration of immigrants who have been granted a residence permit, but are not Finnish citizens. The demand for rapid employment was evident and Finland knew that an influx of asylees and refugees would benefit from the Koto-SIB. This €10 million project attracted strategic partnerships amongst various stakeholders and diverse employment sectors, that enable immigrants to train and work in blue collar jobs. From 2015 to 2016, project evaluators explored blue collar job pathways that would prepare immigrants and refugees to enter the Finnish workforce, by designing a model that would develop an individual’s work life skills, societal and cultural capabilities. Susanna Pieponnen, a senior advisor at the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, who helps oversee the Koto-SIB program, provides insights on the structure of the model, outcomes and some of the lessons learned thus far. We spoke via phone, the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Who was your target group?

Susanna Pieponnen: Our target group: unemployed immigrants between the ages of 17-63, who were ready to work, had a desire and motivation to learn Finnish and accept blue collar jobs. We aimed to target 2,000 individuals over a 3-year period beginning in 2016. The first cohort began in 2016 and currently we are in our 4th cohort.

Tell me about the feasibility and structuring of Koto-SIB. What do you think Finland did differently from other SIB models that target immigrant challenges?

The program aims to place immigrants in jobs within 4-6 months. It is designed for adults who know what type of job they want. The program helps participants learn basic language, navigate cultural settings in the workplace and material that is sector specific. So, it’s very cultural. But mostly, it is flexible.

How is success measured?

The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment will commission an external evaluation after the trial. In the evaluation, the taxes paid and unemployment benefits received by those who participated in the SIB project are compared to the taxes paid and unemployment benefits received by the control group. From the State’s perspective, the trial is a success if the taxes paid by those participating in the experiment are higher and unemployment benefits they received are lower than in the control group. We believe that all parties will benefit, so this is a win-win approach for employers, immigrants, investors and society.

What are some of the lessons learned?

One mistake the government learned early on was assuming immigrants and refugees had to study for a longer period of time and go through a traditional 4-year college. When end-users were asked what they thought of blue collar jobs (ie. drivers, kitchen cooks, hospitality roles), they believed that once a bus driver, always a bus driver. Their confusion about blue collar jobs was contributing to exclusion. Culturally, the jobs were not up to par, but explaining the value of blue-collar jobs and providing them with pathways to advancement, made job placement easier. There seemed to be more understanding of how they could transition from blue-collar jobs to white-collar jobs as we delivered training and reminded them that every job is valuable.

Can the U.S. apply lessons from the Finland SIB model to solve for rapid employment of refugees in the U.S.? If so, why or why not?

The U.S. holds the largest refugee admissions in the world, but recently has welcomed the lowest numbers in its history, with less than 8,000 refugee admissions in 2020. Federal, state and local governments contract with social service delivery organizations to deliver resettlement services, such as job training, English language instruction, similar to the structure in Finland. Refugee admission processes are similar between both countries. Finland welcomes refugees under the refugee quota determined by the state budget; in the U.S., refugee admissions are determined by a presidential determination in consultation with federal and state offices. However, a significant difference amongst the two countries is the timeframe of integration for a refugee. In Finland it is a 3 year process assessed by local employment offices from the day of arrival. In the U.S., a refugee is expected to reach integration within 6-8 months and interacts with multiple service providers. With limited time for integration, the U.S. could use rapid employment advancements as a universal framework. Another key difference is that Finland has leveraged the need of rapid employment as a solution, not a problem. With fragmented funding and a dismantled resettlement program in the U.S., now is the time to revisit the existing gaps of our domestic social inclusion framework and adapt to better solutions.

The first U.S. workforce SIB, the JVS/Social Finance “Massachusetts Pathways to Economic Advancement Pay for Success Project,” is already demonstrating success, both in terms of returns to investors and impact for participants. The SIB launched in 2017, to support 2,000 adult English language learners seeking to transition to employment, higher wage jobs, and/or higher education. Centered around English language needs, the model includes a workforce development component and rapid employment. The Massachusetts PFS model targets English learners who are potentially past the 6-8 month integration period. Both SIB models serve their States’ social inclusion frameworks, however, Finland has implemented the model from initial points of resettlement and integration, whereas in the U.S., it picks up where initial resettlement efforts end. There are many commonalities between both models, so why is this not replicated beyond the state of Massachusetts and integrated to initial resettlement and social inclusion efforts?

As funding for social adjustment programs becomes scarce across all levels of government in the U.S., innovations such as the “Koto-SIB” model, may help serve as a blueprint for local U.S. state governments to advance rapid employment placement and integration of immigrant and refugee communities. The “potential” if applied, could help generate a win-win approach across governments, local communities, emerging employment sectors (e-commerce and agriculture) and investors looking to expand corporate social responsibility (CSR).

*A special thanks to Susanna Pieponnen of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment in Finland and Mika Pykko of The Finish Innovation Fund Sitra, for their support and collaboration.

NOTE: Cristina also spoke about her work with WES Mariam Assefa Fund. Read her interview.

Cristina Alaniz was a student analyst with the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University and continues to be a graduate student at American University’s School of International Service (SIS).

Linkedin: http://linkedin.com/in/cristinalaniz Email: ca3919a@student.american.edu