Looking at the TOPC Process in Long Beach, 2022

Long Beach, located in Southern California around 20 miles south of downtown Los Angeles, has one of the busiest ports in the US. The city’s proximity to LA and the high levels of port activity explain why in 2013, Time ranked Long Beach as the fourth most polluted city in America. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions with the hopes of increasing air quality, the city developed a climate action plan. This plan, which aims to increase tree canopies and utilization of urban parks, also addresses an issue of equity, where low-income communities of color are the ones with the greatest levels of pollution.

For help initiating change, the City of Long Beach approached The Opportunity Project for Cities (TOPC), an initiative of the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation and the Centre for Public Impact.

Since 2020, TOPC has led cohorts of multiple cities and counties through research and design sprints, using open data to address local challenges by bringing together the public and private sectors and centering community voices. As a member of the 2022 TOPC cohort, the City of Long Beach hoped to create a digital tool to increase community engagement and educate the community about the importance of trees, improve the city’s ability to track trees, and make public data more accessible. With knowledge of tree canopies, further research and policy action could then take place.

There are numerous benefits of tree canopy and urban parks, mostly falling into the two big categories of urban sustainability and human health promotion. These benefits include cooling buildings, reducing air pollution, increasing the attractiveness of communities, reducing noise, improving wildlife habitat, and providing recreational opportunities. Urban parks and other community spaces, also called third places or a third space away from home or work, were overlooked in Long Beach, and, at the time of the project, underdeveloped in Long Beach.

Lea Ericksen, the director of technology and innovation at the City of Long Beach, decided to approach TOPC to further the city’s goal of adopting a Climate Action and Adaptation Plan (CAAP). As part of Long Beach’s climate goals, the city proposed to increase urban forest cover, especially in areas that lack tree canopies. This stems from an earlier study in 2006, which found that 14 percent of Long Beach residents, a majority of whom are people of color in low-income communities, were disproportionately impacted and suffering from asthma. This is six percent higher than the U.S. average.

Starting in June 2022, the City of Long Beach, along with community organizations including Puente Latino Association and the Nehyam Neighborhood Association, worked in tandem with Beeck and TOPC partners Google.org and the Centre for Public Impact (CPI) to create a technological solution to help track and measure the data of tree coverage in the city.

In the first stage of onboarding, members completed a systems mapping worksheet to identify relationships between different stakeholders. Vanessa Covington, the climate action fellow for Long Beach, mentioned that government departments have power over the tools, which is probably why there is no connection between individuals and community organizations to the tools. Many times, “people aren’t a part of the data,” but software can help them make informed decisions.

In the second phase, “problem-understanding,” community member input was one of the key components. To gain insight on the challenges of planting trees, interviews were conducted with various residents, arborists, and leaders of various organizations.

Reyna, a Long Beach resident and community worker for development services, highlighted the strained communication between the city government and residents. She recalls that a tree was planted by the city in her front yard without being told about it. She believes that conversations with property owners should occur with the city. In her work, Reyna is frequently asked about vacant lots with the potential for community gardens or parks, and believes that more data and transparency from the city on vacant lots would be helpful in increasing green spaces and community development.

Karina, a student in North Long Beach, said she would get involved in initiatives for urban greening if there were greater opportunities, and pointed out that social media could be helpful to get involved. In the past, she has tried to plant trees, but she feels that the parks can be unsafe, including that there are many people experiencing homelessness and people who smoke in parks.

Hilda Gaytan, the president of Puente Latino Association, believes that the community is estranged. Not having a social connection to neighbors leads to weak community connections. She hopes to bring back community solidarity and wants to work together to find solutions. According to Gaytan, the community does not have time to advocate for climate issues and green space: they want a simple life and want to be with family whenever they have time. Therefore, it is important to meet them where they are at. The community feels powerless fighting against the system, according to Gaytan, and it is vital that the city understands and takes into account their needs to improve the presence of parks and greenspace.

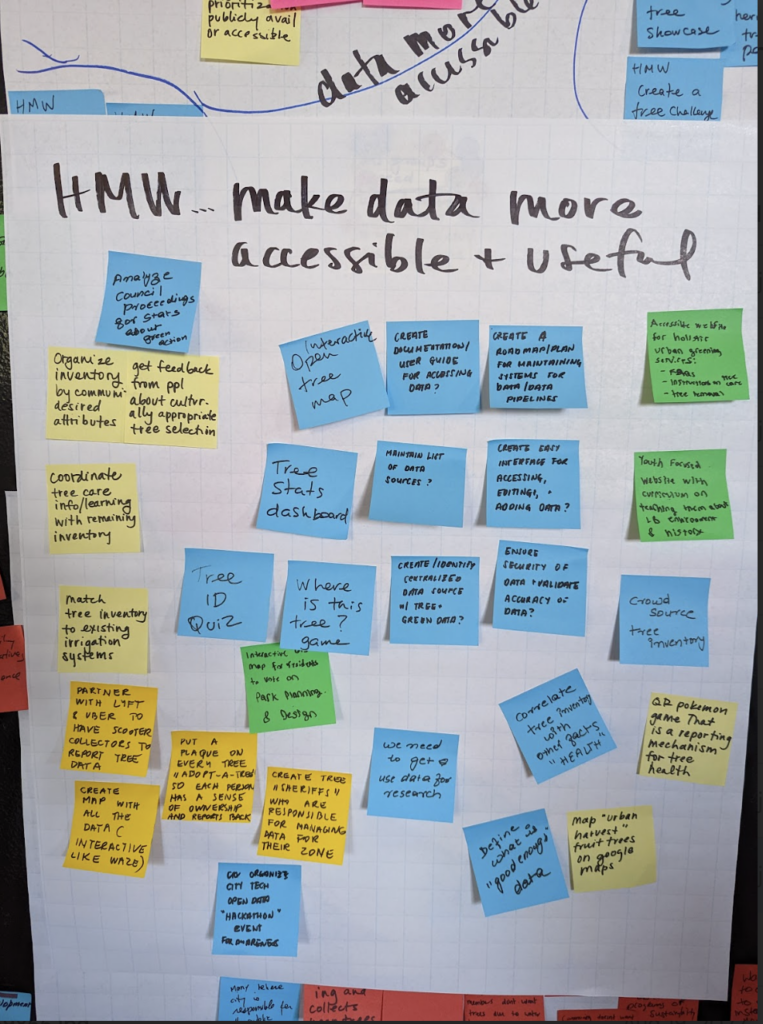

With input from the interviewees, prototyping came next: how can the team implement these ideas to create a tangible digital tool? Human-centered design (HCD), which aims to put the user at the forefront and focus on their experience, was one of the priorities in this phase. Working alongside TOPC, the community members and the Long Beach government were able to prototype a digital tool that collects tree data and residents could join in a community planning event.

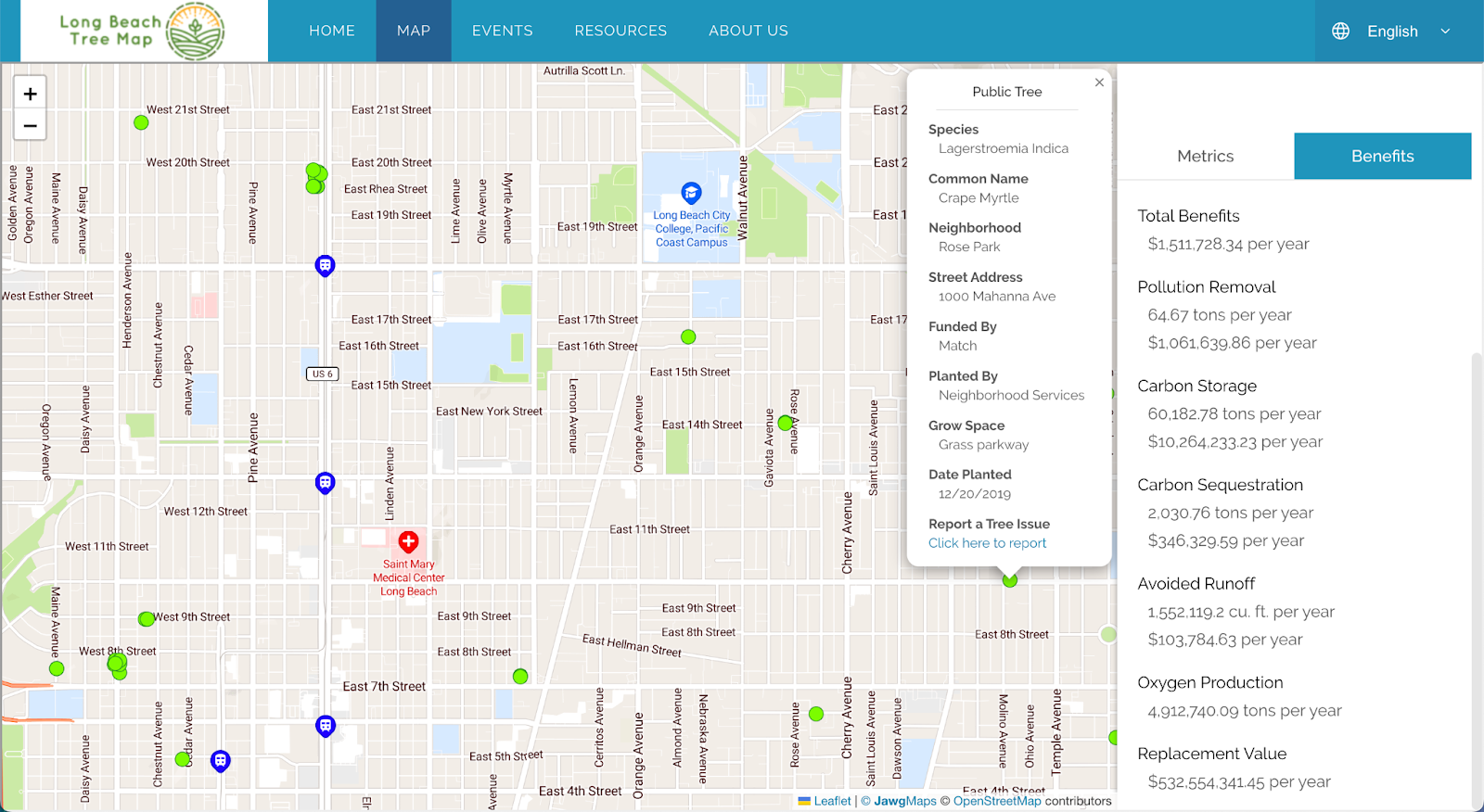

The final product, which launched on November 15, 2022, only five months after assembling the Long Beach team, is the Long Beach Tree Map,. The tree mapper tool uses “open data to improve public health, build climate resilience and address inequities in urban forest access.” The Long Beach Tree Map includes an “interactive tree mapping tool using existing tree data to map out locations for future sites where trees could be planted and maintained via educational engagement.” Moreover, to serve the various ethnic groups in Long Beach, the tool is available in English, Spanish, Tagalog, and Vietnamese.

The potential impact of these solutions ranges from an increase in youth community engagement, community members having a better understanding of the urban forest and how to grow it in a way that works for everyone, creating more opportunities and more understanding for people to participate in urban greening, and a better survival rate for the trees that are planted.

Throughout the sprint, goals changed, visions were challenged, and time remained limited, but one variable remained the same: how could TOPC help Long Beach provide a beneficial service to the community? Together with guidance from TOPC, the core group of community partners, city government employees, and Google pro bono services were able to co-create a digital tool to solve local challenges, centering the voices of affected communities.