Re-engaging Immigrants and Refugees in the Workforce: How Might We Finance This?

June 3, 2020 | By Betsy Zeidman

Khudaier arrived in Austin, Texas as a refugee from Iraq five years ago, with only a high school diploma in hand, leaving a wife and two daughters behind. He found work as a security guard, and drove for Uber, earning $800 a week getting people to and from the airport. When the pandemic shut down flights, and offices closed, like millions of others, he found himself out of work. Like many refugees and immigrants, English is still a challenge, and he made mistakes filing for unemployment, which kept him from having any income until the end of May. He would love to find other work, but building the skills for a different job takes time and money.

Like Khudaier, over 40 million Americans have applied for unemployment since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, and the virus has hit marginalized communities well beyond their share of the population. We know African-American, Latino and Asian-American communities fall ill, and die, at significantly higher rates than white Americans; and can reasonably extrapolate to assume the death rate is high in immigrant and refugee communities as well.

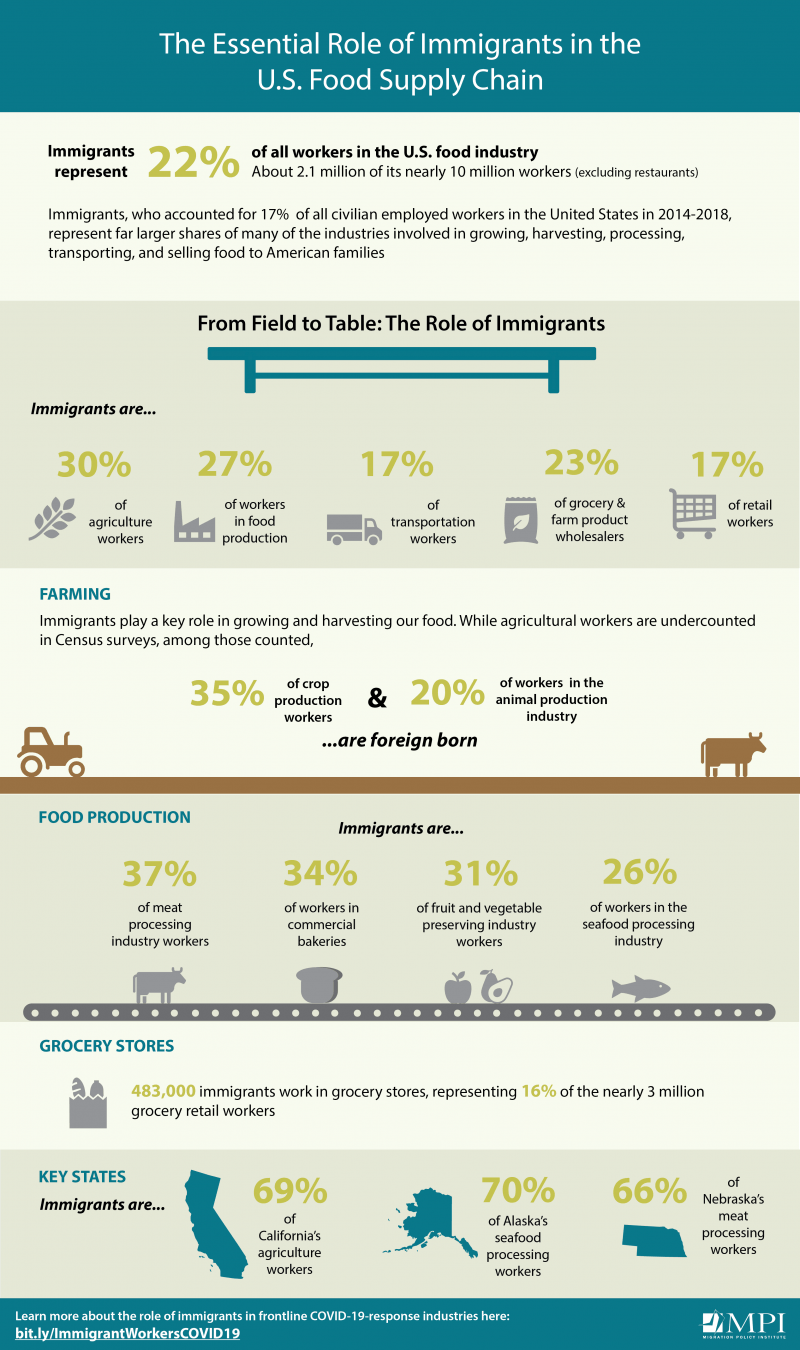

Unfortunately, these communities’ impact on the country is often underrepresented. Just look at how critical they are in getting food on our table:

And that’s not the only industry. While the foreign-born comprise 17% of working civilians they represent a significant component of frontline jobs: 38% of home health aides, 25% of nursing assistants, 41% of janitors, 18% of essential retail (groceries, pharmacies and gas stations), and 34% of bus, metro and taxi drivers. This puts all these systems in precarious positions as these workers rarely have sick leave, have less access to health care, and many live and work in places with little opportunity for social distancing.

Getting our economy moving requires confident consumers willing to spend and healthy workers willing to work. This includes immigrants who are projected to represent 83% of workforce growth between now and 2050. We need these immigrants, but there are challenges to reengaging them in the workforce. Many of these predate the emergence of COVID-19 in the U.S. and are similar to those plaguing native-born people of color. They arise from structural aspects of our economy, such as their over-representation in lower-paying industries. Others include language and cultural barriers. When immigrants do seek to advance, they confront obstacles to obtaining necessary training: lack of funds to cover the cost of training, lack of time off from their jobs, unreliable transportation and sporadic, often costly, childcare. Few are lucky enough to access training through their employer or union if they are part of one.

With the pandemic triggering more remote work and online learning, the barriers grow more prohibitive. Lower-income immigrants are less digitally literate than their higher-skilled counterparts, often lack access to computers and broadband connections. These factors complicate training and make integration into an increasingly digital economy challenging, perpetuating the inequity.

The country needs these immigrants to have a pathway back to work. With the support of the World Education Services Mariam Assefa Fund, we are exploring ways in which the tools of finance might facilitate such training at a greater scale. We’ve built a network of diverse experts in immigration, workforce development and finance. With COVID-19 now a part of all our lives, we are focusing on two areas necessary to enable a safe return to work by immigrants and refugees: workforce training and workplace safety.

Thinking creatively about how to pay for these efforts is even more important now. Government funds (federal, state and local) will be reduced – due to increasing costs of caring for the sick and decreasing tax revenues from the economic slowdown. Blending diverse sources of capital will be important.

While early in our exploration, we have identified some promising models:

- Income-share agreements (ISAs) provide college students tuition in exchange for a share of their future earnings. The San Diego Workforce Partnership, a funder of job training programs, is piloting a new ISA to fund workforce training. They seek a stable, equitable model aligning the interests of workers, trainers, employers and investors.

- Labor-management partnerships support sustainable workplaces that aim to meet the needs of all stakeholders. California-based Building Skills Partnerships connects largely immigrant janitorial workers, their union, and their employers to provide language and vocational skills. Their pioneering Green Janitor Education program set a standard for providing a growth path for this community. With the onslaught of COVID-19 and its impact on janitors, BSP is building an infectious disease training program that, if successful, can be leveraged to other sectors.

- Pay for Success (PFS) programs base payments to training providers on the successful job placement of trainees. Successful efforts link clearly identified target outcomes, proven providers, data collection, cross-sectoral partnerships and catalytic capital. The first workforce training PFS, the Massachusetts Pathways to Economic Advancement, has had early success with entry-level workers and pivoted to a virtual model with minimal loss of participants.

- Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) know their markets as well as any source of capital because they remain so close to their communities. In recent years, they have moved beyond their traditional support of housing and small business to invest in workforce development. Those who received funds from the recent Paycheck Protection Program deployed those funds at a much faster rate than the larger banks.

We know the factors critical to a successful workforce training program: employer engagement to focus on most usable skills; jobs available upon completion; contextualized English language learning, and supportive wraparound services. Linking financing to programs that include such elements will help scale them and bring more immigrants and refugees into the workforce, helping all of us move through the COVID-19 crisis, even as we continue to manage it.

Betsy Zeidman is a Beeck Center Fellow where she explores ways to drive social impact at scale using lessons from behavioral economics, investments in emerging domestic markets and corporate responsibility initiatives.Follow her @BZeidman