The Heart of TOPCities

*pseudonym used

The air felt heavy as Amira* joined her neighbors from the Pleasant Hill Historic District of Macon, Georgia, for a focus group. Frustration mingled with hope as residents described the decline of their once-vibrant neighborhood. Outside, overgrown weeds choked vacant lots, and abandoned homes with shattered windows leaned precariously, as if waiting for the next storm to bring them down. The faint hum of passing cars mixed with the drone of wildlife reclaiming deserted spaces. It was a neighborhood frozen in slow decay.

“This place used to be beautiful,” Amira said. “Now, it feels like we don’t even exist.”

Blight is more than physical decay—for some, it symbolizes neglect. Residents spoke of derelict homes, illegal dumping, and crumbling infrastructure. Children walked past deteriorating houses, asking why their streets looked so unloved. For Amira, it was a blend of loss and fear—fear for the children growing up surrounded by neglect, and fear for her own safety.

“It’s psychological torture,” she said.

For years, residents expressed frustration at the lack of resources and slow response from city officials. “We see accidents waiting to happen—trees falling, wildlife taking over, arson threats,” one resident said. Demolitions erased cherished family memories. “The city owes [these memories] to Pleasant Hill,” another added.

Images 1-2: Examples of severe blight in the Pleasant Hill Historic District of Macon, Georgia. Source: WMAZ (2016) and Macon-Bibb County (2022).

Amira’s story reflects a systemic disconnect between government and the realities of the communities they aim to serve. Historically, civic systems have relied on top-down approaches, with policies and programs designed by experts far removed from the communities experiencing the problems. As a result, these solutions often failed to address root causes or left marginalized voices unheard.

The concept of public participation in civic design dates back to the 1960s, when Sherry R. Arnstein published A Ladder of Citizen Participation. In it, she emphasized the need for genuine engagement, where citizens were empowered as partners rather than as passive recipients of government decisions.

Recognizing this value, The Opportunity Project for Cities (TOPC)—a project of the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation and the Centre for Public Impact (CPI), in partnership with Google.org and the Knight Foundation—embraced human-centered design (HCD) that places real people that are affected at the center of identifying problems and shaping solutions. Inspired by the U.S. Census Bureau’s federal The Opportunity Project, TOPC helps municipalities co-create solutions directly with residents to address systemic issues like housing insecurity, extreme heat, and neighborhood blight.

Since its pilot in 2021, TOPC has engaged more than 1,850 residents through focus groups, surveys, and listening sessions. These efforts ensured solutions were informed by the lived experiences of those impacted and moved at the speed of trust to build long-term change with collective ownership.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

For Kai Fan, a web programmer in Macon-Bibb County, joining TOPC’s second cohort in 2022 wasn’t an obvious choice.

“I was reluctant at first,” Fan admitted. “I already had so much on my plate, and being the only tech person in my department, committing to a long-term project felt overwhelming.” Yet, he was drawn by the opportunity to address challenges in his community, such as neighborhood blight.

Fan’s first project involved co-designing a digital tool to catalog and report blighted properties easily, featuring community feedback at every stage.

“This wasn’t just about tech,” he reflected. “It was about listening, collaborating, and building trust with the community.”

Hear Kai Fan talk about applying community research methodologies to daily work

TOPC’s hands-on learning labs were a turning point for Fan. Monthly workshops taught him equity-centered research techniques and how to engage residents as co-creators.

“The methodologies completely changed how I think about my work,” he said.

In 2024, Fan’s efforts earned him recognition as a Local IT Leader of the Year by the StateScool LocalSmart Awards. One of his proudest moments came from a seemingly simple breakthrough: His team was tasked with addressing how small business owners were struggling to obtain permitting licenses for their businesses.

“At first, we were frustrated and unsure of our direction,” he said. “But through constant communication and collaboration, we found our way. Arriving in one direction was one of the best moments.”

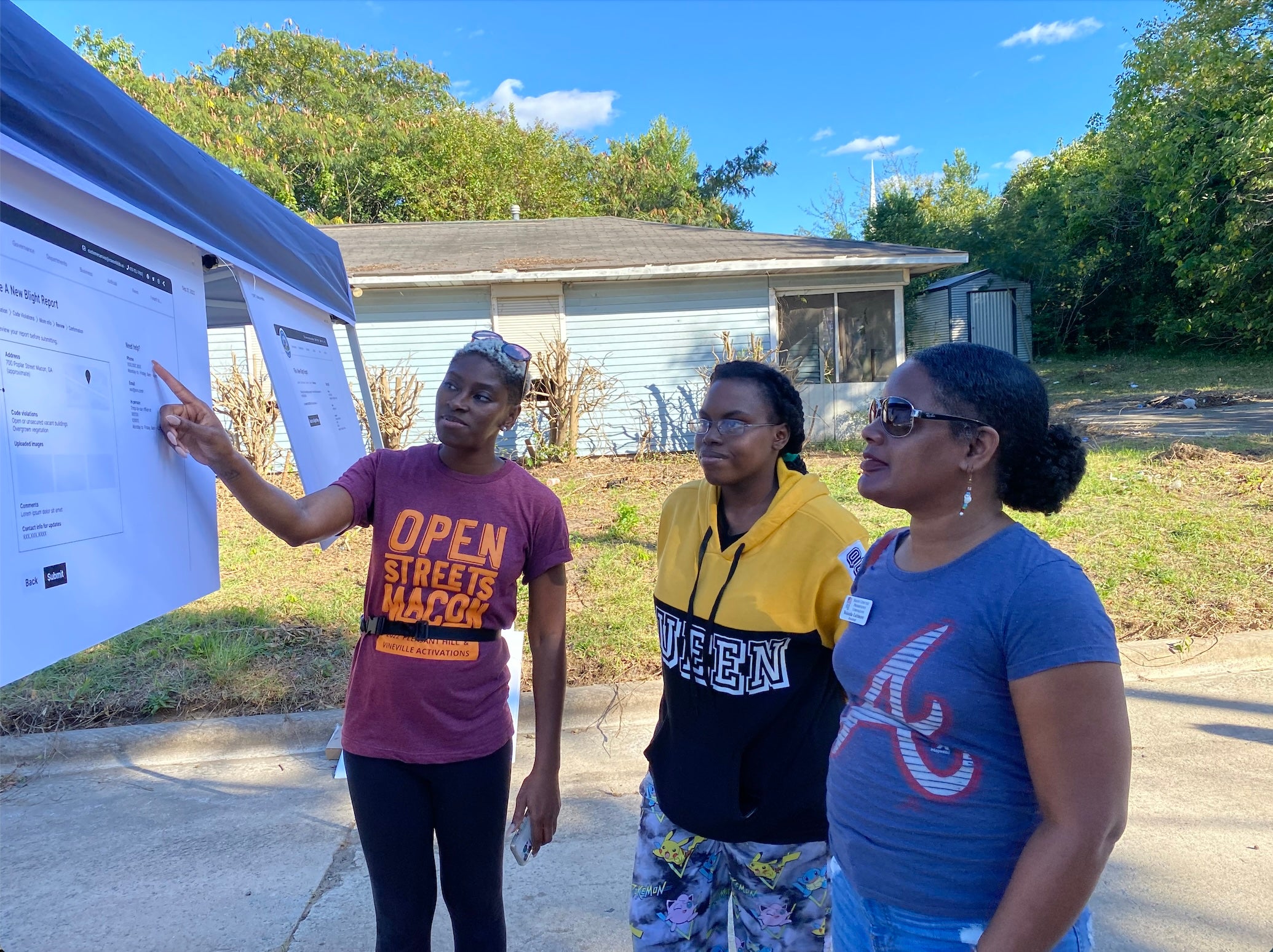

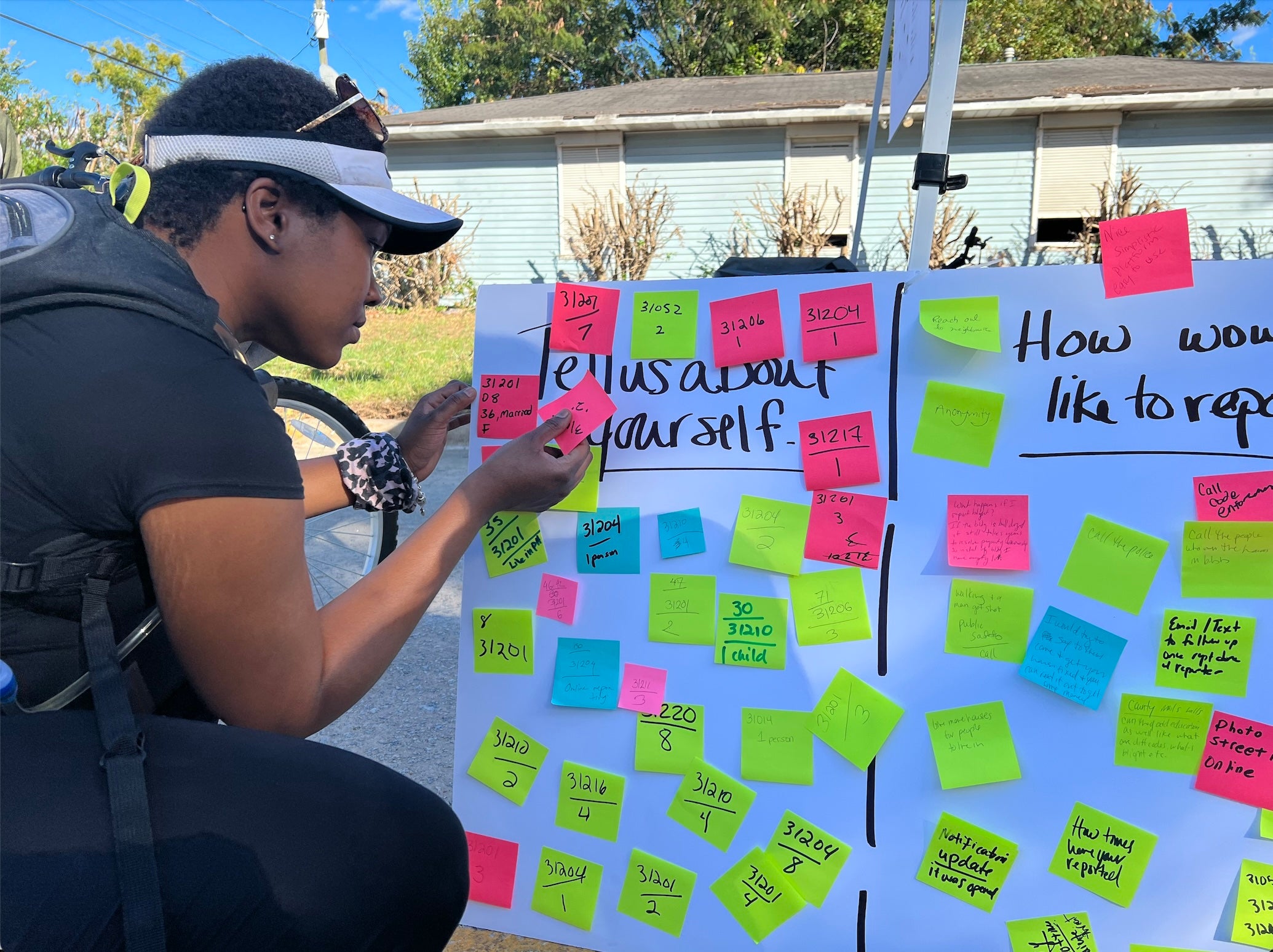

Images 1-3: Pleasant Hill residents participate in a range of TOPC activities, including concept testing and focus group discussions to shape solutions on improving blight in communities. Source: Macon-Bibb County (2022).

TOPC’s approach mirrors a growing need in public service training. The 2021 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS) identified persistent gaps in systems thinking and community engagement—areas where TOPC excels. Inspired by these lessons, Fan applied these practices to other initiatives. “I started considering challenges we hadn’t addressed, like the unique needs of minority-owned small businesses,” he said.

TOPC’s 2024 cohort evaluation showed significant increases in the adoption of HCD concepts in participants’ strategic plans, partnerships, and programming efforts. For example, integrating HCD in partnerships rose from 38 percent pre-program to 88 percent post-program. The results show the positive potential of programs like TOPC in reshaping how local governments approach systemic challenges.

In Miami-Dade County, innovation manager Jorge Valens has always prioritized the people behind the problems to tackle challenges such as energy insecurity and extreme heat.

“The people we serve should see themselves in the solutions we build,” Valens said.

Partnering with Marya Meyer, the executive director of The Women’s Fund Miami-Dade, they streamlined the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) application process. The program’s paper-heavy, complicated application process often delayed critical aid. For many households, this meant enduring Miami’s sweltering summers without air conditioning.

Their collaboration produced a digital tool designed with residents to enhance accessibility and equity. “It’s energizing to hear community members’ perspectives and turn that into a solution,” Valens said. “That’s what makes me happiest—seeing our work stick because it felt alive,” Meyer added.

Their shared goal was not just to simplify the process but to make it work for the people who relied on it most.

“If it’s not working for the people, we should keep working on it,” Meyer said.

For both Valens and Meyer, the most rewarding aspect of their collaboration is the opportunity to iterate and improve. “Every engagement pushes us to test, learn, and grow,” Valens said. “Even if we couldn’t solve everything, like eliminating the need for in-person visits, we proved what’s possible,” added Meyer. “That’s what matters—showing it can be done and inspiring others to push for more.”

Hear Marya Meyer discuss how she leverages community resources to fix broken systems

Collaboration was key to the project’s success. “The program showed us the power of cross-functional teams,” Valens explained. “We typically operate in silos, but bringing together people from different departments and organizations allowed us to tackle challenges more effectively. That always yields magic for fresh perspectives that shape our solutions in ways we couldn’t have imagined.”

In addition to LIHEAP, Valens tackled extreme heat resilience through the Cool Commute project. More than 50 percent of residents in Miami-Dade County live in ZIP codes disproportionately affected by rising temperatures. Commuters frequently cited inadequate bus shelters, lack of shade, and insufficient heat notifications as major issues. Valens’ team created a bilingual, mobile-friendly platform for residents to log transit experiences, helping identify infrastructure gaps in real time.

“Cool Commute wasn’t just about gathering data,” Valens said. “It was about building a platform that gave people a voice and helped decision-makers act on what they were hearing.”

Hear Jorge Valens reflect on how he fostered community partnerships with a resident-focused problem-solving lens

Valens’ leadership was recognized when he was named a 2024 Local IT Leader of the Year alongside Fan. Reflecting on the award, Valens focused on what matters most.

“My legacy is we always keep the resident at the center of our solution,” he said. “Sometimes the solution isn’t technology—and that’s okay. What matters is delivering a positive experience that builds trust.”

Image 1: Image of LocalSmart Awards 2024 featuring Jorge Valens and Kai Fan. Source: Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation (2025).

Carmen Perkins, a Google.org program manager for Google data centers, took on a volunteer role as a UX researcher with TOPC. Partnering with the City of Akron, Ohio, she co-led research for Canopy Connect, a digital tool to combat the City’s declining tree canopy.

Akron’s tree canopy has been shrinking due to development, storms, and limited resources. This decline impacts livability, environmental health, and equity across the city. Many residents often lack the information needed to contribute to greening efforts. At the same time, organizations face challenges in targeting tree-planting initiatives effectively.

Canopy Connect addresses these challenges by transforming Akron’s tree canopy data into a shared resource. The platform enables organizations to identify low-canopy areas for planting initiatives and allows residents to explore canopy data for their city, neighborhood, or property.

For Perkins, the experience was an opportunity to grow and challenge assumptions. “I learned through the program that context matters in the way you present data to your audience, whether it’s for leadership or the public,” she said.

A pivotal moment for Perkins came when she was introduced as an expert from Google during a visit to Akron. Despite initially grappling with the “expert” label, that moment encouraged her to reflect on and reframe her own understanding of expertise.

“I had to ask myself, why would I not see myself as the expert? And what do experts look like to me?” she said.

Hear Carmen Perkins reflect on finding a deeper connection to the communities she served through user research work

Through participatory learning and moments of reflection, TOPC participants have gained insights into unlearning biases. Activities encouraged deeper awareness of their identities and how these influence thoughts, choices, and assumptions.

Matt Collins, a coach from CPI, collaborated with Perkins to guide Akron’s efforts from problem definition to product development.

“I see myself as a convener, helping teams move projects forward,” he explained. “It’s about creating a space where teams feel equipped to replicate this process on their own in the future.”

Hear Matt Collins as he shares his journey of rediscovering his passion for creating meaningful learning experiences

TOPC’s 2024 evaluation highlighted significant gains for both participants and coaches like Perkins and Collins. Knowledge levels rose across all HCD skill areas, particularly in experience design, strategy, and measurement and evaluation. Before the program, only 58 percent of participants reported high confidence in applying HCD concepts. Post-program, this figure increased to 94 percent.

“I’ve learned a lot from participating in the research process,” Collins said. “My role as a convener helps build ownership for the teams we support.”

Looking ahead, Collins envisions lasting impact. “We offer a unique experience for teams,” he said. “We help them lift the work in ways that allow them to replicate it down the road.”

Perkins agreed about the program’s value for both residents and civic practitioners. “This program motivates employees who are often underfunded and understaffed. It helps them feel like they can keep going,” she said.

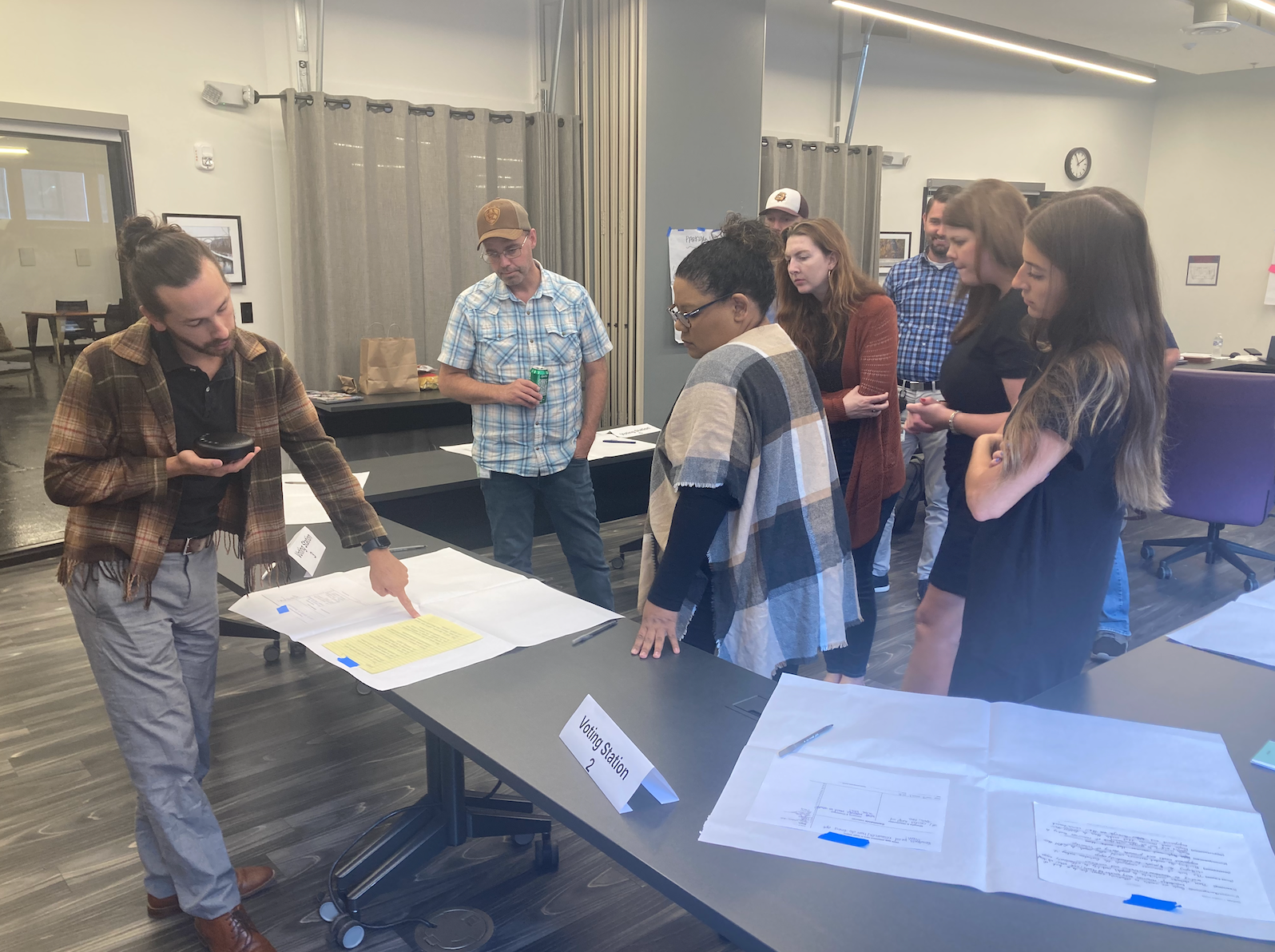

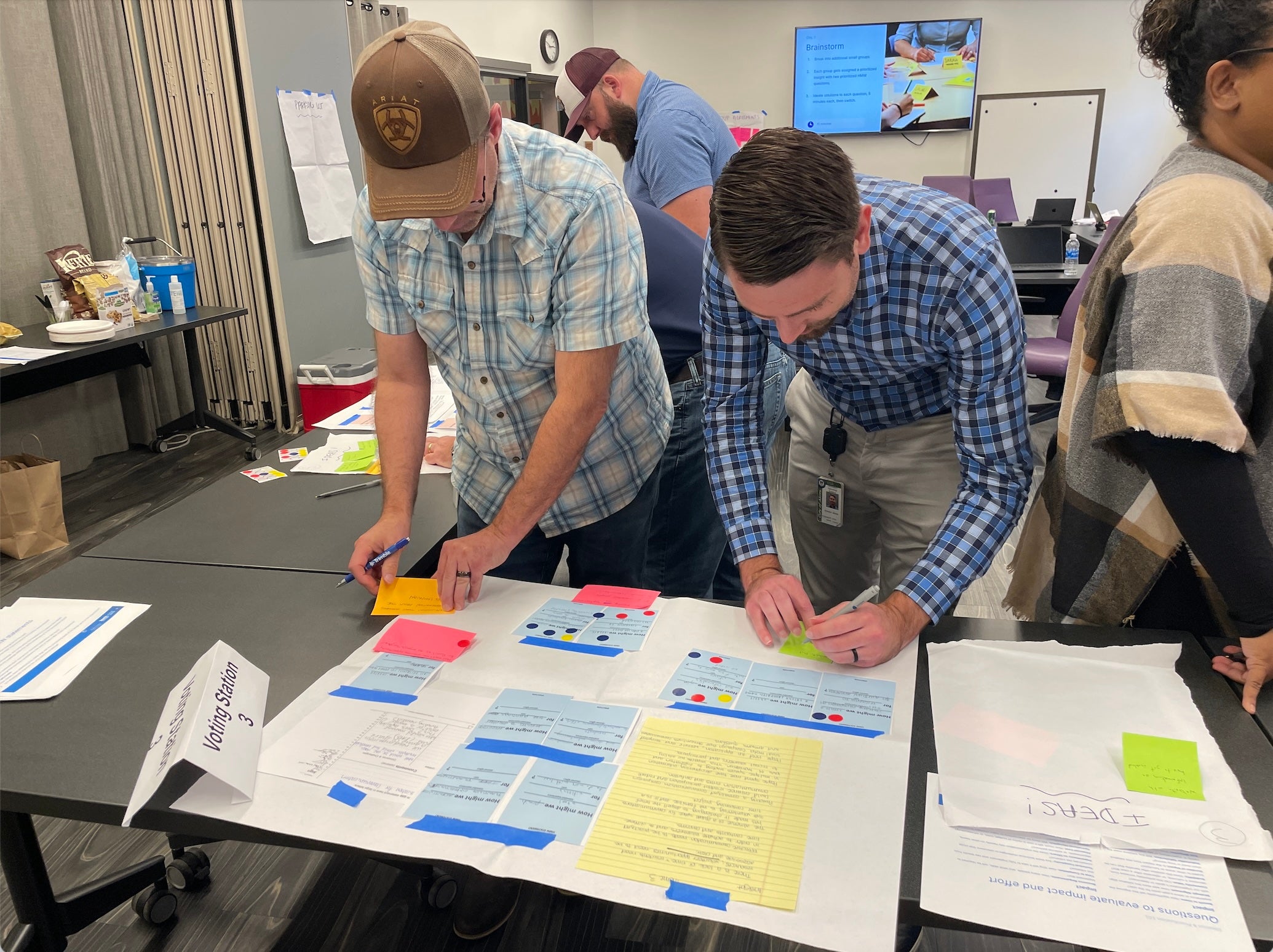

Images 1-2: City of Akron employees participate in TOPC journey mapping workshops. Matt Collins and Carmen Perkins co-facilitate sessions to ideate and sketch solutions. Source: City of Akron (2024).

The scale of TOPC’s impact is undeniable. Since its inception, 108 local government employees from eight municipalities and 35 departments have participated. These efforts were supported by 137 Google.org pro bono technologists and 20 community-based organizations.

Harold Moore, director of the TOPC program at the Beeck Center, highlighted what made the program stand out.

“Our programs matter because they provide dedicated space for municipalities to experiment and learn without the constraints of lengthy hiring or procurement processes,” he said.

Moore described TOPC as a safe place where governments can test ideas, take risks, and develop tools without fear of failure. “When municipalities are engaged, motivated, and well-resourced, amazing things happen quickly. Resources find their way, people show up for meetings, and community connections strengthen.”

In Akron, the Canopy Connect project gained momentum even after the program concluded, with a full launch planned for April 2025. At the December 2024 Tree Commission meeting, representatives presented their findings, and tied their work to the Commission’s goals of outreach and community engagement.

In Macon-Bibb County, TOPC research led to the launch of a blight reporting tool to address the systemic neglect residents like Amira had long endured. The tool empowered neighbors to report blighted properties more effectively, while providing actionable data for the county. Paired with a $750,000 grant to revitalize public spaces in Pleasant Hill, the initiative began to breathe life back into the community. More than 400 residents took part to create a vision for their neighborhood’s future.

“At the end of the day, it’s about cultivating relationships,” Collins said. “The relationships we’ve built are the foundation for sustaining this work.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Special acknowledgements

The Beeck Center’s TOPCities would not have been possible without the Knight Foundation’s support, the Centre for Public Impact’s guidance, and Google’s talented technologists provided through the Google.org Fellowship program. Most importantly, we honor the residents, community leaders, and local government employees who trusted us and the process. Thank you for inspiring us all.