Workforce Training of Immigrants and Refugees: How Can We Pay for It?

This is part 2 of a series. Read Part 1

September 21, 2020 – By Betsy Zeidman, Cristina Alaniz and Iliriana Kaçaniku

Since America’s inception, immigrants and refugees have come to the U.S. in search of a better life. They settle with or near family and seek employment using the experience they bring from their home countries. They may access resources provided by government or social service agencies, or in the case of refugees, resettlement agencies. They receive services for a set number of weeks and success is determined by how many find a job upon completing the program. But little incentive exists to find a “quality” job, that is, one with equitable benefits and compensation, support in and out of the workplace, and growth potential. They often end up working in grocery stores or as home health aides, and are frequently overlooked by their customers and clients.

But this may be changing. The global COVID-19 pandemic has refocused our country on the value of “essential workers,” and heightened awareness of the large numbers of immigrants and refugees that compose this workforce. At the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation, we see the many barriers these workers face in trying to integrate and advance in the workplace, and the long-term impact of such barriers on our society and economy as a whole. With the support of the World Education Services (WES) Mariam Assefa Fund, we have explored expanding the economic integration and mobility of immigrants and refugees through financing workforce training.

Recognizing that this is a multi-faceted challenge requiring multi-faceted approaches, we recently convened two meetings of individuals, intentionally selected for their diverse expertise in workforce training, immigrant integration and finance. During the first session, we focused on development and training programs and identified a number of best practices for programs serving this population. Our second session explored ways to finance effective training programs, which we summarize here.

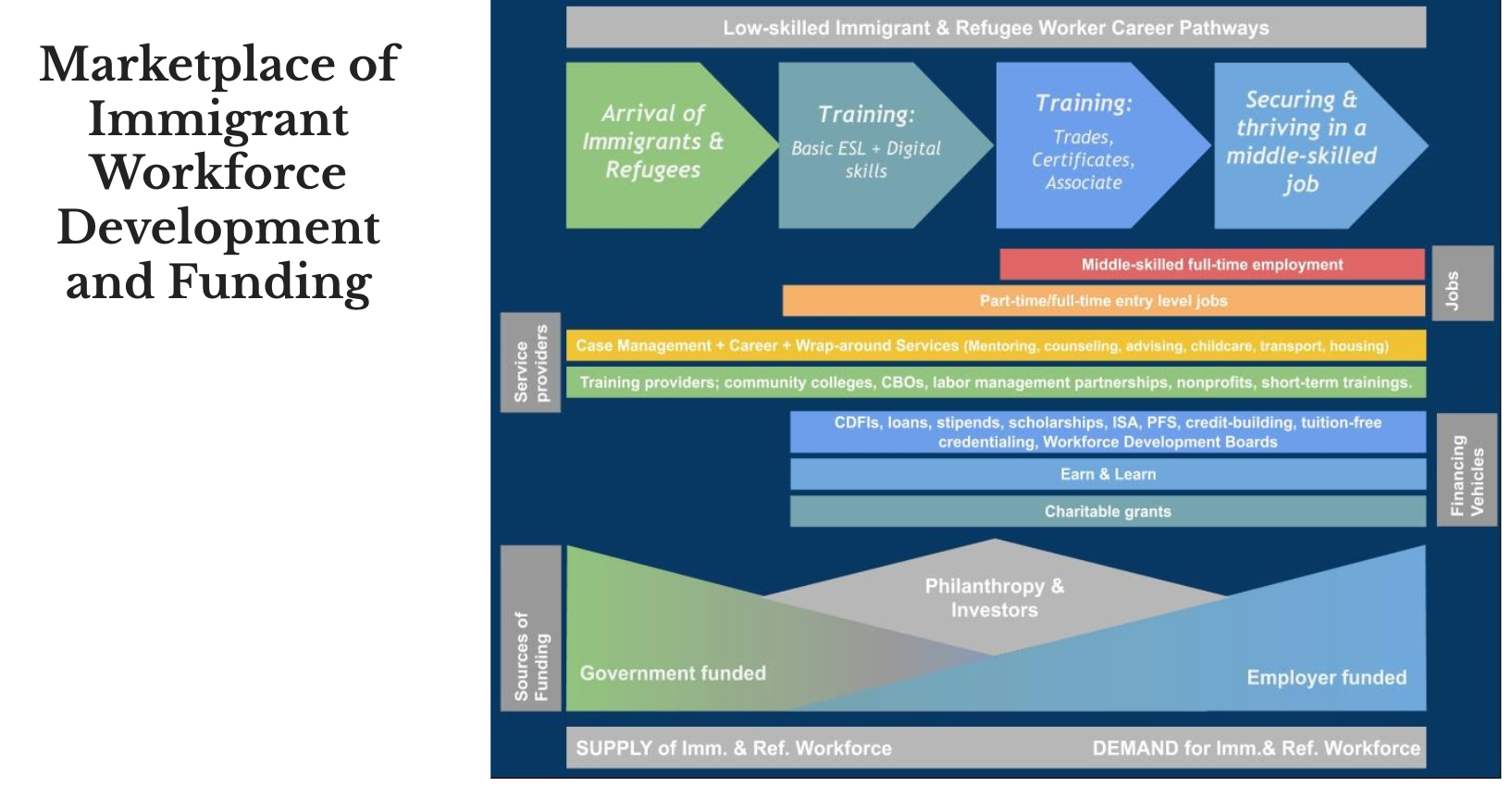

The workforce development field is large and scattered with many players and fragmented funding, with the path for immigrants and refugees even more complex (See Figure 1). We also have little data on many critical elements, such as how many immigrants and refugees participate in workforce training programs (as they are not tracked as a discrete group); and how much it costs to train a worker (as important ancillary costs are rarely tabulated). We do know that money for these programs comes from government (federal, state and local), philanthropic grants, the immigrants themselves, and employers seeking to upskill their workers – with some supporting the programs and some offsetting the cost to workers. These funds then get distributed to organizations through charitable grants, loans, “earn & learn” apprenticeships, public-private partnerships, and more. Together, these financing efforts are important, but a large capital gap remains, as workforce development’s demand for funds simply outweighs its supply.

In seeking options to fill that gap, discussion participants agreed that capital supporting workforce development programs should be patient and flexible; how to find and deploy such capital is the question. There were multiple options, but six key recommendations emerged.

Clarify the problem, identify the program(s) that could solve it, and then determine the most appropriate source and form of capital to cover the cost. Discussions around funding often submit to the lure of innovative financing vehicles that can become overly complex and difficult to implement, and organizations lose sight of the problem at hand – immigrants and refugees need quality jobs, and employers need trained workers. Focus on those needs first, and then figure out the best funding tool.

Structure financing to reward and incentivize measurable outcomes. If the goal is higher wage jobs, establish benchmarks for measurement, track data rigorously, and share results. Pay-for-Success (PFS) models champion this type of outcomes-based financing, and there are several workforce PFS pilots underway. Two examples include:

- The Massachusetts Pathways to Economic Advancement Social Impact Bond (SIB) raised over $12 million from private investors to front the cost of expanding vocational English language lessons designed for immigrants & refugees in Boston. Launched in 2017, investors received returns early, and trainees saw increased earnings as measured by administrative wage data.

- Philadelphia Works, the city’s Workforce Development Board, is piloting a slightly different SIB, one that trains workers for a single employer. The employer (in this case, Comcast) is the ultimate payor, reimbursing the non-profit based on preset targets for both employment and retention. A third party monitors and measures results. Comcast’s involvement at the outset ensures that the training supports actual jobs.

- There are also publicly funded programs that tie payment to performance measures. For example, Texas State Technical College receives payments from the state based on the earnings of its students over their first five years post graduation.

Align financing with growth. These variations on the PFS models use growth as the proxy for success and help mitigate risks to the trainee. Examples include:

- An Income Sharing Agreement (ISA) allows people to enroll in education programs for low or no cost, and pay tuition over time as a share of their earnings. These have traditionally been the province of students in 4-year college programs and challenged due to their high interest rates. The San Diego Workforce Partnership (SDWP) is piloting a student-centric ISA: interest rates are reasonable and no repayment is due until a student’s annual salary is at least $40,000. SDWP is the first Workforce Board to try an ISA.

- The Career Impact Bond (CIB), developed by Social Finance, is similar to the ISA and the SIB, as it draws together a wide variety of stakeholders (employers, training organizations, donors and investors) to advance economic mobility among overlooked communities. The model integrates incentives and aligns risk among all parties:

- the training entity fronts some of the initial costs, with repayment from investors;

- high quality training for sectors in need of workers (in this case IT) maximizes job placement;

- building in philanthropic support allows the CIB to finance wraparound services (linked to higher completion rates), and

- student-centric terms similar to those used by SDWP increase repayment.

- Revenue-Based Models: Where ISAs enable individuals to access training and pay for it once they generate income, revenue-based financing allows commercial entities to access capital and repay it once they generate income. This financing (also known as royalty financing) could serve as an alternative to debt for training organizations that support immigrants and refugees (and is of particular interest to Muslim immigrants whose tradition rejects paying interest). However an organization must have a clear plan to generate revenue, e.g., a contract to train the workforce of a stable employer.

Braid in different streams of capital – public, philanthropic and private – in two key ways:

- Staging: Program needs evolve over time, so staging sources and structures of capital may make sense. Government and philanthropy support training for basic skills, such as English language learning. As workers seek more specialized training, employer support kicks in.

- Blended Models: Workplace solutions increasingly appeal to impact investors and foundations seeking opportunities for mission-related investments. A blended capital fund may support a training program, where sources with low- to no-return expectations (e.g., philanthropic funds’ program-related investments) could absorb risk that private capital generally wouldn’t bear.

Research all available pools of capital. Important sources of capital for workforce training and development can sometimes be overlooked or underutilized, so supporters should be sure they are looking into all available options. A few examples include:

- Government funds resting in federal, state and local programs. For example, many community colleges providing workforce training can receive funding for administrative services from SNAP E&T (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education and Training). SNAP E&T also covers a student’s tuition and fees, and a portion of ancillary expenses, such as books, dependent care and transportation, as do Pell Grants. Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) channel funds to local workforce departments.

- Equity to help build businesses that provide or support training, participate in purchasing cooperatives and make investments in social enterprises that provide critical support services.

- Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) as useful (and underutilized) partners. They exist amid the targeted populations and know the communities’ needs. They are patient and flexible, and often provide a bridge to mainstream capital. In the recent economic crisis, they have been invaluable and are largely limited only by their size.

Keep it local. Local community partnerships can finance effective, sustainable workforce training programs. As an example, the Alamo Colleges Westside Education and Training Center is a specialty campus for workforce development of immigrants and refugees on the West Side of San Antonio, Texas. It represents a collaboration among the city, local economic development department, community college, school district, small businesses, nonprofits and funders, and offers targeted academic programs and social service services. When the last Levi’s plant closed the facility became available and the full community rallied. Government, foundations, and employers provide financial support.

In partnership with the WES Mariam Assefa Fund, the Beeck Center began exploring effective ways to finance and expand the economic integration of immigrants and refugees through workforce training a little over a year ago, when the world was a very different place. The arrival of COVID-19 clarified the importance of these efforts, and highlighted areas of opportunity, including:

- We must get better data on the immigrant and refugee population. They are not simply a subset of low-income communities.

- We know that these efforts work best when all stakeholders have skin in the game, so we must embed such mechanisms into partnerships of all sorts: labor-management partnerships; public-private partnerships; community collaborations, to name a few.

- We know the field needs patient, flexible capital, so we must tap the ultimate patient capital, philanthropy. However, funders must not simply hand over grants. They should lean into risk mitigation and use their funds to catalyze the participation of new providers of capital.

- We must determine which outcomes-based models work best, and for whom and replicate those with attention to each market’s local context.

- We must consider the systemic issues that hinder immigrants and refugee workers, and advocate for incentives that support pro-worker programs.

- We must remember that amid all these challenges, opportunities exist for those who remain aware. For instance, the Building Skills Partnership (BSP) recognized that before businesses could reopen after the COVID19 quarantine, they would need deep cleaning and sanitizing. Given the numbers, this would create a huge demand for workers. The Labor-Management Partnership created a program to train its janitors to meet this need.

We look forward to sharing these and additional lessons we’ve learned over the past year, and hope to help inform the broader diversity of stakeholders in the workforce development field as they move forward.

Betsy Zeidman is a Fellow in the Fair Finance team at the Beeck Center

Iliriana Kaçaniku is a Consultant in the Fair Finance team at the Beeck Center

Cristina Alaniz is a Student Analyst in the Fair Finance team with the Beeck Center.