Taking Steps Toward Digital Transformation

The digital transformation of government is a powerful idea. It has sparked great enthusiasm and speculation about how technology and data might revolutionize government efficiency, policy-making and service delivery. But despite significant investments and innovations, these promises have not yet delivered at scale.

To better understand the limits and potential of digital technologies in American government, the Digital Service Collaborative (DSC) at Georgetown University’s Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation[mfn]The Digital Service Collaborative (DSC) is a program designed to develop research around government digital services, create tangible resources for practitioners, cultivate the community of digital service leaders in governments to share and scale efforts, and explore policy considerations including ethics and privacy. The DSC team is based out of the Beeck Center at Georgetown University, supporting public and private sector efforts to responsibly share and use data to address some of society’s most challenging issues and to support civic engagement with public institutions. See https://beeckcenter.georgetown.edu/project/digital-service-collaborative-building-capacity-for-digital-transformation-in-government/, accessed 21 October 2019.[/mfn] spent five months talking with people working at the frontlines of digital transformation in US cities, counties, states, and federal agencies.

A full description of background, methods and findings from this research are presented in the 37-page report: Setting the Stage for Transformation: Frontline Reflections on Technology in American Government.

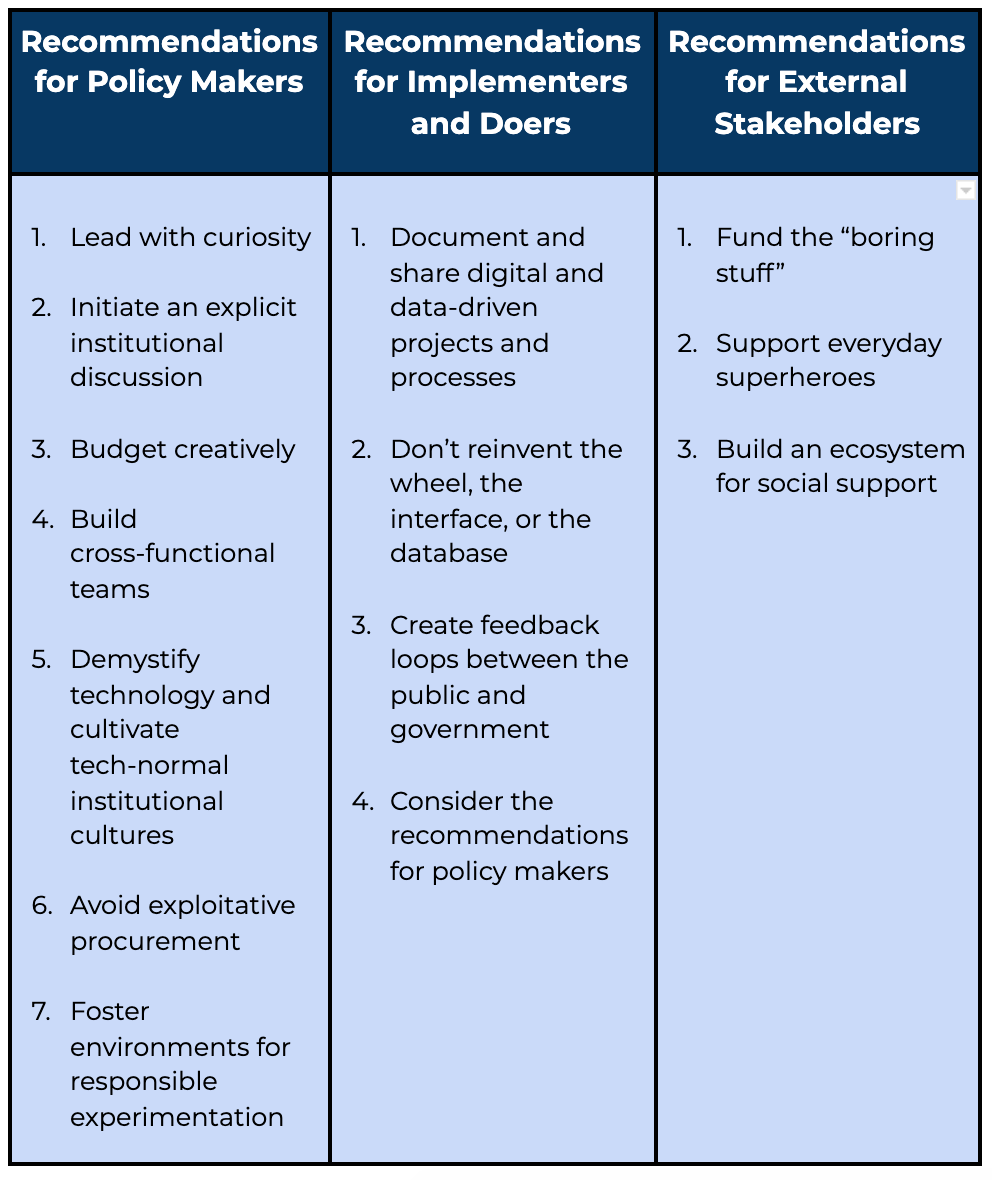

Key findings and recommendations are presented here, including the following recommendations:

A summary of these recommendations and the research on which they are based is presented below in three sections.

- The first section describes how people working on the frontlines of American government experience the limits and potential of technology more generally.

- The second section describes the above recommendations in greater detail.

- The final section provides a brief description of the research methodology and context in which this should be considered.

Understanding Transformation

18F defines digital transformation according to three characteristics of a transformed government institution: the connectedness of staff to an agency’s mission, the application of technology toward that mission, and agency commitment to continued improvement.[mfn]Pandel et al., “Best Practices in Government Digital Transformation: Preliminary Report.”[/mfn] Responses to this research supported that view, but also described digital transformation as more of a journey than a destination. This is best summarized in the following three arguments:

- Digital transformation is an iterative and evolutionary process, in which new tools and strategies are applied and demonstrate value incrementally, opening space and interest for additional tools. No single tool or strategy ever immediately transforms an institution.

- Digital technologies are an instrument for improving government and not an end in themselves. The objective behind implementing any digital tool, product or associated process is and should always be providing better government and better government services to the public.

- Digital technology is embedded in contemporary governance; it cannot be avoided, nor should it be fetishized. As a descriptive term, “digital government” makes as little sense as “paper government.” To effectively adapt to the new technological context in which they necessarily operate requires government institutions to acknowledge that using digital tools is the new normal.

In keeping with these arguments, respondents viewed digital transformation as something that could and should be managed by people working in government, in order to improve government and the services it provides. In particular, respondents described multiple benefits and contributions that the smart use of technology and data could provide to (a) civic interaction and service delivery; (b) data, evidence and analytics; and (c) efficiency and resources. Respondents also described numerous specific obstacles and barriers posed by (a) insufficient capacities or resources, (b) formal rules and institutional structures, and (c) institutional cultures and preconceptions.

Respondents described an interaction between short term benefits of using technology, and the long-term changes to institutional practice and culture that would enable more scaled and widespread use of technology to improve outcomes. This interaction is how respondents described processes of digital transformation in government institutions.

When describing what enables such processes, respondents described three broad institutional conditions:

- Explicit support for cross-functional technical expertise

- Deliberate professionalization of technical expertise, and

- Open and engaged institutions.

In order to facilitate these conditions, and set the stage for meaningful digital transformation in government institutions, this analysis makes fourteen recommendations to policy-makers, implementers, and external stakeholders.

Recommendations

Recommendations for policy makers

- Lead with curiosity. There is often an esoteric quality to the types of tools and strategies referenced in this report. This makes them easy to dismiss, underestimate, or in some cases, it can inflate expectations. Leaders in government should take time to explore and understand the roles, skills and ways of working that are associated with the strategies described here, and the value that they can add to policy and service delivery. Doing so helps to maximize their value, and to signal that value across institutions, while also strengthening coherence across teams and setting realistic expectations.

- Initiate an explicit institutional discussion. This might take any number of forms, including an audit of existing practices, setting up a task force to review opportunities, or simply asking technical staff to begin holding brown bag lunches. The important thing is to create a space in which new ideas and approaches can be suggested and considered, with a real potential for implementation. The context of this discussion could also vary widely. A good checklist can be drawn from the “seven lenses of transformation” proposed for defining and benchmarking transformation by the 7 UK Government Digital Service.[mfn]Vickerstaff and Cunnington, “How to Set up Transformation Projects That Could Shape Our Future.”[/mfn]

- Budget creatively. The cost of technology can be inhibitive. Engage technical staff to identify ways in which implementing digital can cut costs elsewhere. What processes could be automated to free human resources? What paper processes can be digitized to eliminate printing and transporting costs?

- Build cross-functional teams. Identify ways to avoid responsive silos of technical expertise by integrating technical and non-technical expertise in teams and processes. Create opportunities for technical and policy experts to collaborate across project cycles, from planning to evaluation, even in projects where technology or data play a minor role. When possible, aim to establish cross-functional and co-located teams in order to strengthen learning and cross-pollination between technical and policy expertise.

- Demystify technology and cultivate tech-normal institutional cultures. Identify opportunities for trainings, hosting events, or inviting speakers that can communicate the nuts and bolts of relevant data and technology. Cultivate an institutional environment that values frank conversations about technology and its limits, and that does not fetishize technical expertise at the expense of other expertise.

- Avoid exploitative procurement. One of the most profound ways to limit the cost of technology programs is to avoid overpaying on technology procurement. Contacting peer institutions that have made comparable investments and conducting more thorough market research can help.[mfn]Brethauer, “Announcing OASIS Discovery: Making Market Research Easier.”[/mfn] It may also be possible to pursue cooperative procurement,[mfn]See, for example https://www.nigp.org/home/find-procurement-resources/directories/cooperative-purchasing-programs, accessed 21 October 2019.[/mfn] modular contracting,[mfn]Jaquith, “Prerequisites for Modular Contracting.”[/mfn] or to piggyback on existing contracts with other government agencies or institutions.[mfn]See https://www.coprocure.us/about.html, accessed 21 October 2019.[/mfn]

- Foster environments for responsible experimentation. Attention to the novel risks that accompany technology and data often focus on challenges to privacy and consent, but also involve more subtle ethical risks, such as poorly informed policy or the opportunity cost of wasted technology budgets and processes. Explicit institutional processes and attention during planning and analysis phases can help to identify and mitigate these risks, and can be integrated into several of the other recommendations presented here.[mfn]For a detailed description of a process-based approach to managing risks associated with government data, see Wilson, 2018. For a collection of applied tools, see the Responsible Research and Innovation Toolkit at https://www.rri-tools.eu/about-rri, accessed 21 October 2019.[/mfn]

Recommendations for implementers and doers

- Document and share digital and data-driven projects and processes. The demand for storytelling and experience sharing is widespread and consistent across the front lines of digital transformation. Conferences and events provide a much-needed forum for inspiration and “therapy” — as well as learning and education — but there remains a need for technical documentation for the types of projects that are implemented in multiple jurisdictions. Make a point of documenting technical specifications, steps taken, challenges and processes along the way. Share this.

- Don’t reinvent the wheel, the interface, or the database. There is a significant degree of replication in government technology. Conduct market research to determine what similar platforms and products have been created by others.[mfn]The Federal Source Code Policy supports reuse and public access to custom-developed Federal source code, which is published at https://code.gov/about/overview/introduction. Organizations like 18F and Code for America also often publish detailed documentation and descriptions of digital tools (see https://18f.gsa.gov/2016/04/06/take-our-code-18f-projects-you-can-reuse/ and https://www.codeforamerica.org/news, accessed 21 October 2019.). International resources, like the International Development Bank’s repository of off-the-shelf technology solutions may also be useful (see https://code.iadb.org/en, accessed 21 October 2019).[/mfn] Modify and adapt open source solutions when appropriate. Produce and share open source solutions whenever possible.

- Create feedback loops between the public and government. Most digital services imply an opportunity to solicit feedback from users. Leverage this to collect input for continually improving those services. Ensure that users can see how their input is received and that they feel heard. Look for opportunities to publicly respond to feedback, building confidence and trust in government.

- Several of the above recommendations for policy makers can also be relevant, especially regarding procurement, creative budgeting, demystification, and responsible experimentation.

Recommendations for external stakeholders

- Fund the “boring stuff“. Grants and resources tend to flow toward what seem to be the most novel and exciting projects, like blockchain and machine learning products, which are often untested, unproven and not what government leaders will say they need most urgently. Often, the kinds of digital and data-driven innovations with the greatest potential to transform government and government services can sound a lot less exciting, and struggle to find support. Developing common data identifiers across agencies or moving data from servers in a closet into a secure cloud environment are examples of work with revolutionary potential, but for which it is difficult to secure funding.

- Support everyday superheroes. Several respondents pointed out that the most important and transformative work isn’t always being done by the usual suspects on the civic technology conference circuit. Some of the most impactful support may involve doing research to discover who is already naturally advancing digital transformation in state and local government, without recognition, and what kind of support they need to scale their successes. In the words of one respondent, discussing the limits of support to CIOs, CTOs, and CDOs, “C-suite only gets you so far. You need to focus on the people in the field.”

- Build an ecosystem for social support. Dedicated support to specific projects is important, but much of the work to enable digital transformation involves more sharing and learning across institutions. To the degree that this is already happening, it is happening organically. Gatherings such as the annual Code for America Summit[mfn]See https://www.codeforamerica.org/events/summit, accessed 21 October 2019.[/mfn] provide prominent fora for digital service professionals to gather and share, as do internationally focused events and communities, like those surrounding the Open Government Partnership[mfn]See https://www.opengovpartnership.org/ accessed 21 October 2019.[/mfn] and the international open data community.[mfn]Christopher Wilson, “Open Data Stakeholders: Civil Society.”[/mfn] The movement of experienced digital service experts through the agencies and institutions they support is also seen as an important, if limited, mechanism for building community and spreading awareness. The digital service delivery community should create more opportunities and modalities for government champions to engage with and learn from their peers, both in person and online.

About this research

This research was designed based on the conviction that the individuals doing hands-on work to bring technology into government best understand technology’s potential and limitations. These individuals do the hard work transforming government. Their work isn’t always the most exciting or shareable, i. It sometimes results in compromise and failure. But it is from this perspective that we can best understand what technology can do to improve government, and how to manage the risks and challenges along the way.

To better understand the perspectives, the DSC team collected data and conducted interviews between November 2018 and March 2019. This included a desk review of more than 80 articles, reports, and policy briefs, semi-structured interviews with more than 70 individuals, and informal consultation and planning conversations with more than a dozen professionals and organizations. The data collected from this process was reviewed during a three-day synthesis workshop in March 2019. A detailed description of the methodology is provided in the full report: Setting the Stage for Transformation: Frontline Reflections on Technology in American Government.

A note on the research context for digital government transformation

This research builds directly on the foundational efforts of New American Foundation’s work on Public Interest Technology and government innovation,[mfn]Schank and Hudson, “Getting the Work Done : What Government Innovation Really Looks Like”; Muñoz et al., “Public Interest Technology: Closing out Year One and Looking Forward to Year Two.”[/mfn] by focusing specifically on the experiences of front-line civil servants and policy makers. It makes an effort to deepen that work by attending to the role of individuals at multiple levels of government and in multiple policy areas.

In doing so, this analysis departs most research on the digital transformation of government, which adopts a global perspective and emphasizes the work of national level digital service teams.[mfn]Bracken and Greenway, “How to Achieve Sustain Gov. Digit. Transform.”; Eaves and McGuire, “2018 State of Digital Transformation.”[/mfn] Much of that work is also relevant to this analysis, however, and should be considered in future research transformation processes in American institutions. In particular, recent work by Ines Mergel and colleagues has suggested a conceptual model for linking the drivers, objects, processes, and outcomes of digital transformation,[mfn]Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug, “Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews.”[/mfn] and four propositions regarding the sustainability and impact of digital service teams.[mfn]Mergel, “Digital Service Teams in Government,” 10–11. A summary of the four propositions suggests that the effectiveness of digital service teams is related to their centralization of decision authority, that the duplication of practice across teams increases the likelihood of adoption elsewhere, that increased formalization of teams increases their capacity to scale and likelihood of standardization of practice, and that the acceleration of organizational change increases the likelihood of standardized and successful innovation practice.[/mfn] These may provide useful frameworks for designing and evaluating specific applications of technology to institutional processes in future research.