Getting the Most Out of Design Research

December 18, 2020 – By Emily Tavoulareas

Last month, I facilitated a conversation as part of the Beeck Center’s Ideas That Transform Series with colleagues working on a project to improve outcomes for older youth in the foster care system. While our discussion focused on their recent research which they have published today, I found myself thinking a lot about the approach they took to their research—combining a “discovery sprint” with design research—that led to a fundamental shift in both how they thought of the problem, but also the possibilities for solutions. Here I dig into some lessons that can be drawn from their experience, that might be applicable to solving problems in any context.

The approach

The project was run by Think of Us, a small non-profit working to transform child welfare, to better understand how a product or process intervention might improve outcomes for youth as they age out of foster care. Bloom Works partnered on the execution. The project took place in less than 16 weeks (though not consecutive). They did a “discovery sprint” coupled with design research—two things that are relatively common in the technology arena. What this example demonstrates is how powerful this approach can be when applied to entirely non-technical problems.

What it boils down to is that this type of research… really puts people at the center. It brought that proximity not just to a product—but to, how is it that my humanity exists within this bureaucratic web of decisions that are affecting my life?

– Sixto Cancel, Founder + CEO of Think of Us

What I find most compelling about this effort is that while they had a clear research question to begin with, what the team learned changed the way they saw the problem space at a fundamental level. So the project team adjusted their focus in-flight. Here are a few key lessons from their approach, that could be helpful to anyone endeavoring to do this type of work.

Lesson 1/ Be open to going beyond your original research question.

The team started their research focused on identifying insights that were relevant to the product that Think Of Us set out to build. They quickly realized that what they were learning had implications that went far beyond that technology. What they were picking up on had the potential to change the entire equation at a fundamental level in a very real way.

Although these may seem like things that are obvious–they weren’t… there were these “aha moments”—these epiphany moments. – Sixto Cancel

Instead of confining themselves to their original research goal, the team gave themselves permission to allow the learning to drive where they took the work. The research plan was intentionally semi-structured—it meant that the team went into the sprint with a set of topics to guide interviews and observations, but allowed room to explore additional lines of inquiry as they arose. Had they been inflexible, they would have risked rooting the research in the wrong question and, as a result, identifying ineffective (or worst, harmful) solutions.

Lesson 2/ The intervention will never be a system

As they began the research, the team considered the child welfare system overall as a part of the solution, and sought to find ways for the system to drive change. However, as Think of Us CEO Sixto Cancel said:

“… the biggest epiphany and pivot was understanding that no matter what, the intervention will never be a system… systems are cruel and people are kind… and that the *real* intervention is the human beings that are in the system. The system has a way of setting conditions that make it easier, or very hard, to be able to engage in those relationships.”

The research allowed them to get beyond specific actions and experiences and understand the systemic conditions that were robbing young people from engaging in the very life-affirming relationships that can support their time in and out of foster care.

Lesson 3/ Commit to your goal, but be flexible on the process

“You always approach a project with a perfectly designed research plan, methods, recruitment techniques… and then you hit first contact with reality and it kind of unravels in a variety of ways.” – Sarah Fathallah, Independent Designer and Researcher for Bloom Works

The team adapted a great deal, and doing so unlocked significant insights. Their ability to stay focused on the goal but adjust their approach in flight enabled them to learn from their interviewees, go deep on their experiences, and uncover unspoken motivations and beliefs.

A perfect example of this was the team’s plan for recruitment. Originally, they planned to “snowball” (that’s when you interview one person and they introduce you to others) their way into interviewing youth’s supportive adults. But they quickly realized that young people didn’t *want* to introduce the people closest to them. While that required a new plan for interview outreach, it was also an insight in and of itself—youth were so protective of their close, trusted relationships that they refused to introduce them to the system. It was a transformative insight and completely changed how they thought about the problem space.

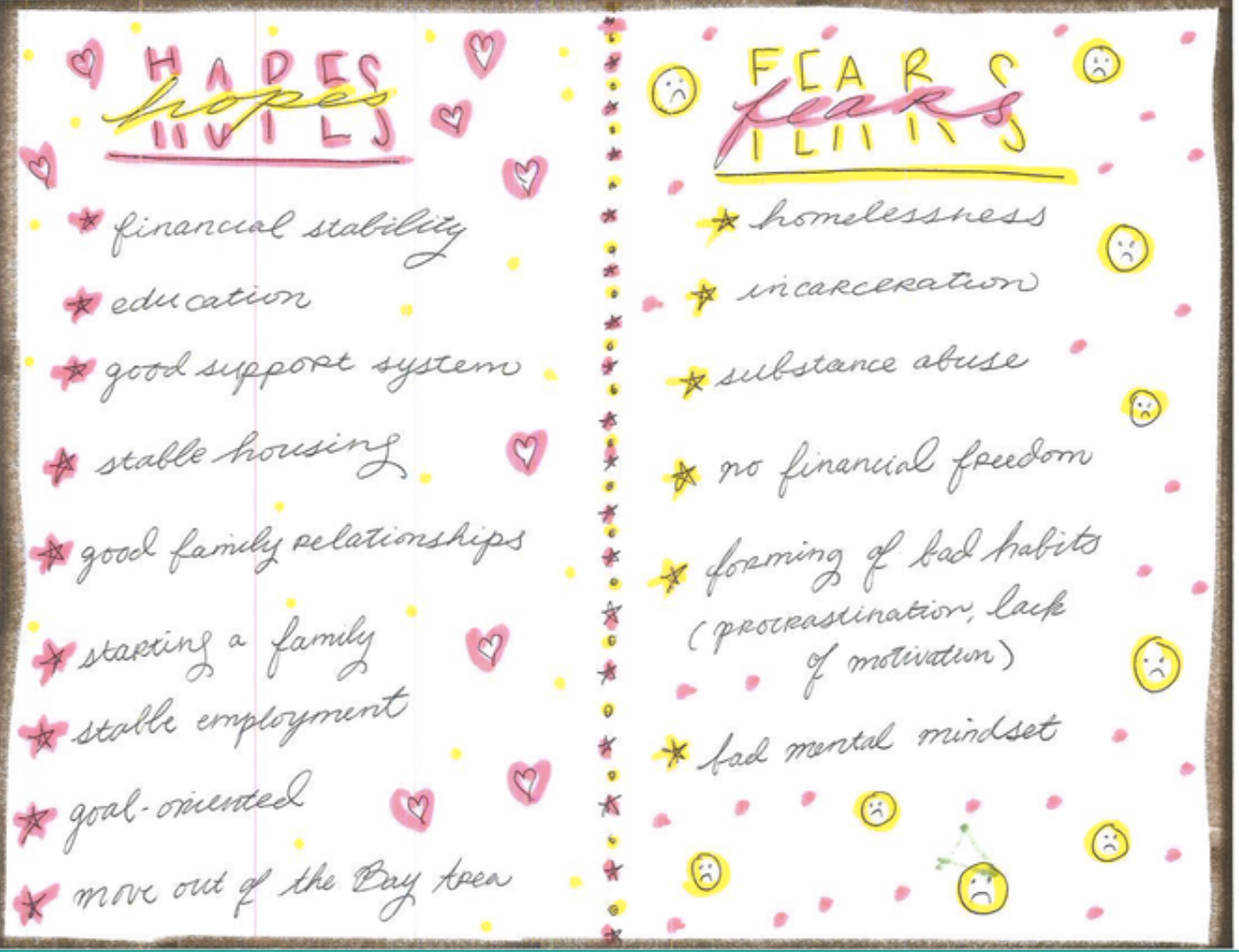

In another example, the team needed to reframe workshop scenarios and questions in order to get participants to talk about what would best support them in their transition out of foster care in a way that didn’t just mimic how they were repeatedly told by the system to think about that transition. To do so, the team tasked them to list out the hopes and fears they have about growing up, then imagine the app that could alleviate those fears and make their hopes come true. This meant focusing on their strengths and resilience, and getting beyond the stories of loss and hardship that often define them. Something as simple as imagining an app can help make children’s dreams feel more realistic.

Lesson 4/ Trust the process

“This work requires a different evolution of yourself, because you have to question every single thing you might think you know about a problem.” – Sixto Cancel

While it is true that this approach has transformative potential, it is also true that it’s extraordinarily messy. It’s a non-linear process that attempts to bring order to unstructured information, and requires comfort in (or at least tolerance of) ambiguity. As designers like to say—you have to “sit in the mess” and “trust the process.”

That “mess” is both tangible and intangible. In its physical form it is an explosion of sticky notes, quotes, sharpies, and laptops. In its emotional form it feels a bit like crushing doubt and anxiety: What are we doing here? How are we going to pull anything insightful out of this mess? How is **this** helping youth in any way? I really just don’t see where this is going. I personally still have moments like this every time I am neck-deep in synthesis. For those experiencing it for the first time and having to trust their partners leading the effort, the feeling is real and unnerving. But the reason we say “trust the process” is that it does have a way of getting where you need to go—often with unexpected outcomes.

Lesson 5/ Be mindful of your positionality

“We were aware that (1) we are strangers, (2) that we held more power, (3) that we were coming in pre-endorsed with whatever reputation the youth had of their agency, as we were introduced by them, so whether that was positive or negative, we were ascribed those values immediately.” – Sarah Fathallah

One of the keys to effective interviews—of any kind, but especially in design research—is trust. This team was very thoughtful and intentional about their relationship to the youth they spoke to, considering questions like, “How do we gain trust? How do we make this relationship a little bit less extractive than it would usually be?”

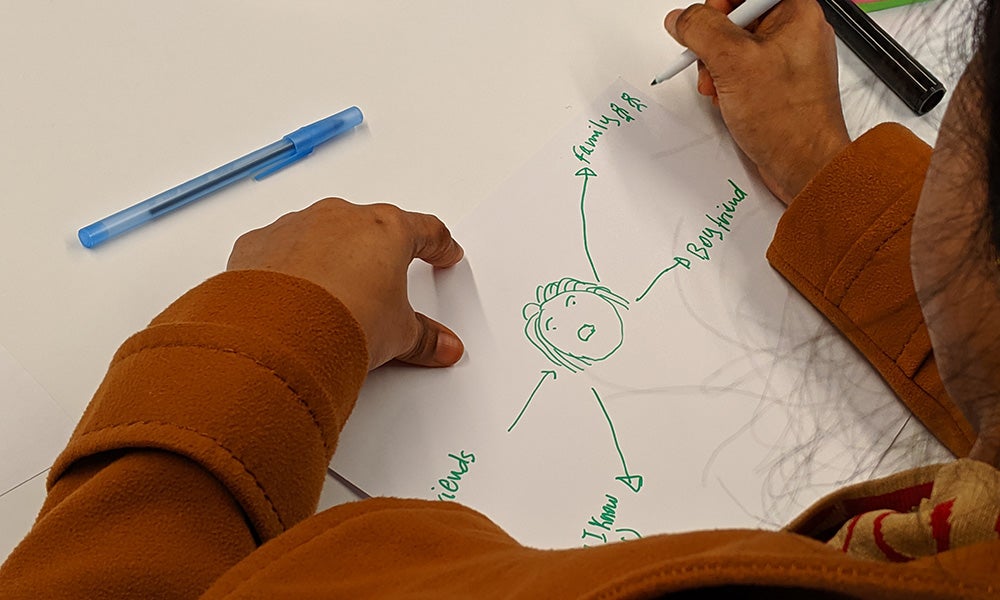

This took them beyond the typical subject-researcher relationship, and aimed to make it more of a partnership. This meant giving participants a sense of agency by having them control components of the research process. This included opting out of activities, stopping at any time, skipping questions, and agreeing together on the agenda of a participatory workshop before diving in.

Another way the research team built trust with interviewees was to find ways to demonstrate respect—compensating them for their time and wisdom, and setting up an environment that feels comfortable and less formal by decorating and rearranging the space, having snacks and craft supplies, and dressing casually.

The ability to stay focused on what the team aimed to learn, and adjust along the way in pursuit of that understanding, made it possible to identify solutions that were both valuable and practical.

Watch the full panel discussion with Sixto Cancel, Sarah Fathallah, Sarah Sullivan, and Emily Wright-Moore. See more from our Data + Digital Mini-Series

Emily Tavoulareas is a designer and a fellow at the Beeck Center. Follow her at @EmilyTav.