How to Get Started in Public Interest Tech: Recommendations for Recruiting Early-Career Tech Talent

September 10, 2019 | By Jillian Gilburne and Dennese Salazar

Student Analysts Jillian Gilburne and Dennese Salazar produced the report How to Get Started in Public Interest Tech: Recommendations for Recruiting Early-Career Tech Talent. The following is an edited version of their findings.

There is a point in every college student’s academic career when they begin to wonder what it’s all for…. It might be the sense that using a freshly minted computer science degree to perform A/B testing on app interfaces feels soul sucking — or they can’t get past the cognitive dissonance of using their design chops to help kids make healthier school lunch choices one day while designing marketing materials for a fast food empire the next.

While we know this sounds dramatic, it comes from personal experience. In joining the Beeck Center this summer, we realized that we had the opportunity to use our newly obtained knowledge and networks to highlight opportunities for careers in public interest technology and design that combined technical skills with social good.

While some experts have indicated that the public interest technology movement is currently going through its “tween years,” when tasked with designing a research capstone of our own, we wanted to take on a topic that would be important for the sustainability of this field through its adolescence and into its adulthood — the recruitment of young technologists into public interest and public sector jobs. We wanted to create a project that would allow us to focus on how to better assist early-career job seekers interested in civic tech and government service design positions.

Much like the popularization of “public interest law” in the 1960s and ’70s, the possibility of a career in “public interest technology” is rapidly winning over the hearts and minds of university students seeking to make an impact in their professional lives. However, in the status quo, many recent graduates are encouraged to start their careers in the private sector and circle back to government after they have gained some experience through the tour of civic service fellowship models offered by the Presidential Innovation and Management fellowships, TechCongress fellowships, Code for America fellowships, New Sector RISE fellowships, or other similar programs. While many before us have found this to be a totally fulfilling pathway, we know that the government’s need for technical skills is rapidly outpacing this approach. And we also know that entry-level job seekers like us don’t necessarily want to start in the private sector and come in through a fellowship — we’re looking for careers we can start and grow in these great civic organizations.

According to a 2017 NextGov Survey, there are four times as many government IT specialists over the age of 60 as there are under 30. In California, 38% of current Government IT employees are at retirement age or will be within five years. While recruiting top tech talent requires government agencies to compete with well-resourced private sector recruitment teams, organizations like Coding it Forward have proven that younger generations have a strong interest in using their technical skills for good.

The Design Challenge

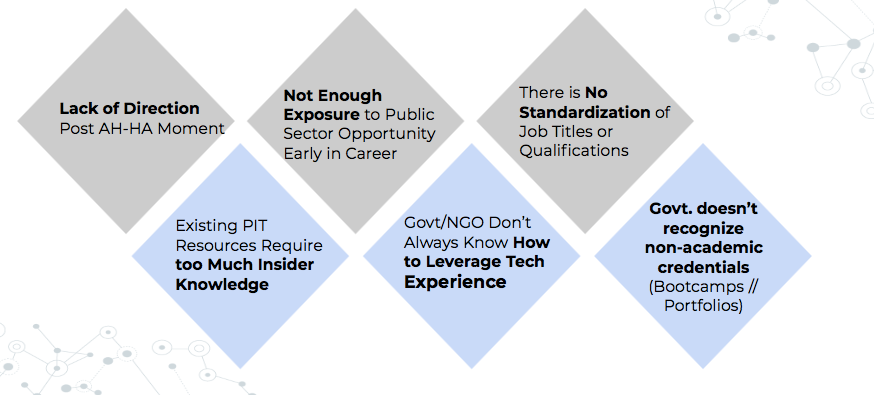

Faced with a problem as nebulous and multi-faceted as rethinking the way early-career technologists are recruited into public interest and public sector roles, we started by breaking the project into smaller pieces. We outlined our project objectives, stakeholder and assumption maps, and research methods, and conducted hours of precedent research and interviews with representatives from Code for America, the New America Public Interest Technology University Network, Design Gigs for Good, the team that runs the federal government’s employment website USAJOBS, and the Georgetown University Cawley Career Center. After learning more about the issue area and synthesizing our research, we broke our findings into six major problems facing early career professionals wanting to pursue a civic technology or digital services career:

Major problems our research and interviews surfaced based on the status quo for early-career job seekers who are interested in public interest technology.

To address these problems, we came up with three phased approaches that includes focusing on changes with job boards, career centers, and government teams.

First We Started with the Job Boards

Recognizing that the government hiring process was not something that we could fix overnight, we decided to focus our project on stakeholders who we had access to and who had some degree of agency over their piece of the puzzle.

We started with job boards since they are an obvious entry point for newcomers starting their civic tech journey. Our research was prompted by the belief that job boards can be doing more to orient potential recruits and build up interest in the absence of well-resourced public sector recruitment strategies. After a series of interviews with public interest job board managers and user-experience research with ourselves and other job seekers, this is what we found:

Context

A major barrier facing the public interest technology recruitment pipeline is that new job seekers often lack context for what their future career might look like. While resources and university partnerships have been developed by organizations like Code for America and New America, newcomers don’t always know where to find them or that they exist. Given that job boards are often the most public facing and frequently used pages for some of these organizations, we believe that they can function as translators between public interest and public sector tech organizations and new job seekers.

Representation

As entry-level people begin their career searches, location and work environment often have major influence on the decision-making process. The existing Code for America job board and the data science microsite on USAJOBS have an emphasis on featuring civic technologists with diverse backgrounds, which we greatly appreciated, but we also want job boards to emphasize geographic diversity. Currently, many of these job boards recruit predominantly from large cities, like San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C. While the geographical distribution of jobs is a larger and more complex issue than we could address in a few weeks, we believe that job boards should be doing more outreach to organizations and local governments in smaller, less well-represented cities.

Pathways

A common misconception that students and entry-level job seekers have is that their career journeys have to be linear. This belief makes the blurred boundaries of public interest and public sector technology especially overwhelming. Because there are so many ways to use technical skills in government or to support public interest projects, there is no formal “pipeline” or “pathway” for newcomers to follow. To combat this, we are proposing that job boards create “are you new here?” pop-ups with links to resources, instructions for access online civic tech communities, and fellowship opportunities.

Toward the end of July, as we carried out an ideation sticky-note session, we began to think about overarching recommendations that would aid job seekers. Photo by Dennese Salazar.

Toward the end of July, as we carried out an ideation sticky-note session, we began to think about overarching recommendations that would aid job seekers. Photo by Dennese Salazar.

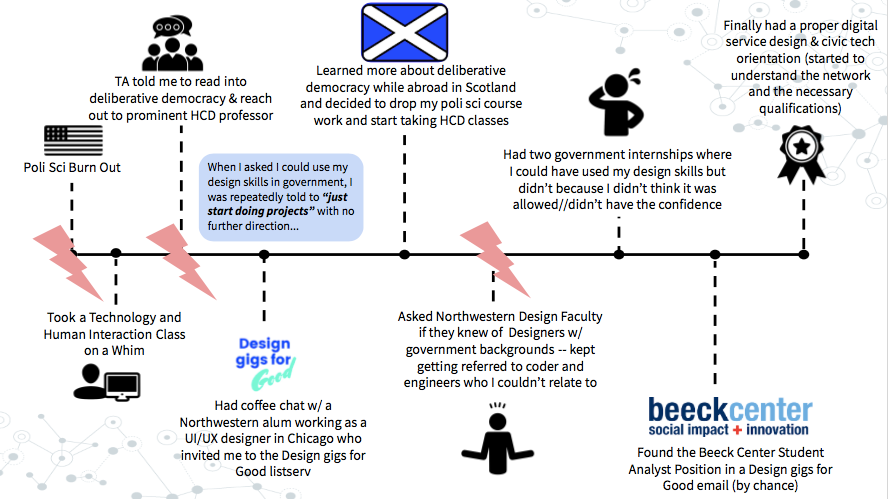

Then We Consulted with the Career Centers

Through our interviews with the New America Public Interest Technology Network and the Georgetown Cawley Career Center we realized that civic tech barriers start earlier than interactions with job boards. As a current student and recent graduate, we have had firsthand exposure to the discrepancies between public and private university recruitment strategies, and we know that a handful of professors do most of the labor when it comes to providing civic tech specific advice and resources to students. To better understand the design opportunities within the university context, we mapped out our own journeys into this space and made note of the pain points where we could have benefited from clearer guidance.

In order to better understand how we could help university students access the civic tech space, we mapped out our own experiences to identify pain points.

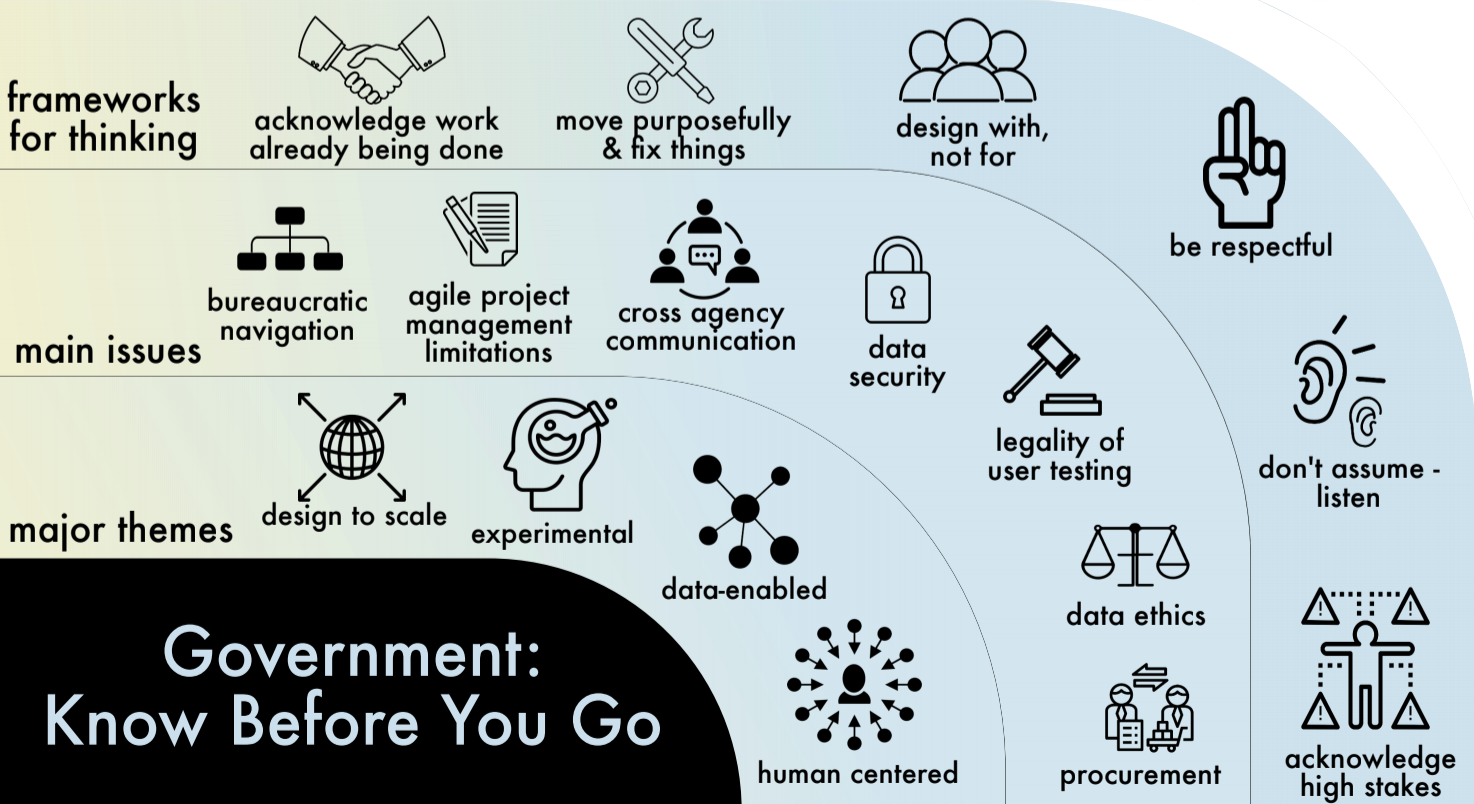

The final product was a “How to Get Started in Public Interest Tech” guide, designed to introduce, entice, and break down what we think a student would need to get started.

We used recruitment materials from a dozen different civic tech and digital service organizations to put together a list of the most common civic tech roles, scraped 91 job postings on Code for America’s job board using an open source word analytics software to put together the most frequently requested skills, and interviewed current practitioners to develop a better understanding of what civic tech work looks like and the pathways to it.

Our goal was to not only make something that a student could understand, but also a guide that faculty or career service professionals could use to recommend public interest technology to their students.

This is a subsection of our student guide that maps out some of the thematic takeaways we learned during our summer working on civic tech at the Beeck Center.

This is a subsection of our student guide that maps out some of the thematic takeaways we learned during our summer working on civic tech at the Beeck Center.

And Finally, we Pitched to Government

We know that we are not the first people to take on this project — in recent years, the Office of Personnel Management redesigned USAJOBS, the White House proposed a legislative plan to overhaul federal HR services, and the organization Coding it Forward has placed young tech talent across federal agencies during the past three summers. However, based on the insights and recommendations we collected throughout our research, we have compiled a list of changes that we believe governments could make to help early-career tech professionals find their way into public service.

First, we think that government agencies should take a cue from recruitment techniques used by the private sector. This could include resume books, which are collections of resumes compiled by a university based on a particular semester and industry that are then sent to employers seeking employees. This would shift the burden of reaching out to desirable applicants to government hiring managers, but also the likelihood of agencies finding a perfect fit. Or increased career fair presence at universities across the country, to ensure that the public sector is able to establish relationships with top talent. This method would include thinking more intentionally about how to convince young people that working in the government will help them to hone their skills and develop new qualifications. Given the skyrocketing cost of tuition and student loan debt, extending federal scholarship programs to tech, design, and management degrees might also help the government agencies compete with the allure of Silicon Valley.

Second, there are a number of reforms that could be enacted during the hiring process. This could include creating direct hiring permissions for technologists and designers across the agencies — this model has already been tested to recruit short-term cybersecurity experts. This process is not commonly practiced in the status quo due to its complexity and human resources offices with various agencies not knowing of its existence. While more research and clarity is needed, our hypothesis is that this shift would make the recruitment process faster, ensure that those who understand the requirements of the job have more of a say, and bring in temporary hires who could prove the value of a more long-term hiring strategy for technical talent. We also think that developing microsites like the USAJOBS pages for data science and cybersecurity could help to provide specific direction for federal job seekers with in-demand technical skills, and might be a model for further standardizing job posting language across agencies.

What’s next?

For us, taking on this problem through our capstone was deeply personal. During our summer on the Beeck Center’s Data + Digital team, we have been exposed to an innovative and diverse community of technologists and do-gooders who are working to hack and bootstrap our democracy. They work across different sectors, on different topics, and came to this line of work and this community in a multitude of different ways.

Our capstone project as part of Beeck’s Digital Service Collaborative, an effort in partnership with The Rockefeller Foundation, has been working to support unification efforts to increase idea sharing and mentoring across a decentralized public interest technology ecosystem, and we hope it will contribute to the ongoing efforts to reduce barriers of entry for university students and early-career professionals. We know that this work is instrumental to the sustainability of the civic tech community in the long term, and we look forward to a future where young technologists seeking out government positions is the norm.

—

Dennese Salazar was a Summer 2019 Student Analyst supporting the Data + Digital team who recently graduated from Brown University.

Jillian Gilburne was a Summer 2019 Student Analyst supporting the Data + Digital team and will return to Northwestern University this fall where she will be a senior majoring in Communication Studies, Political Science, and Human-Centered Design. Follow her on Twitter @JillianGilburne.